ELKADER — Service was a family affair for the Witt clan during World War II.

At 105 years old, Marjorie “Marge” Witt Costigan is a living testimonial to that.

She is the last surviving sibling of four brothers and sisters who served during the war.

Marge and her sister Elizabeth “Sis” Witt Monks, served in the U.S. Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) during the war.

Their brothers Don and William, both served in the Army. Both ended up in the Battle of the Bulge. Don served in an armored unit. William, a medic in the 106th Infantry Division, barely evaded capture by the Nazis. He was taking an injured soldier to an aid station when his unit was overrun.

“Grim years,” Marge said.

It was a time of great worry, Marge says, but doing one’s duty was never questioned.

Marge, a graduate in history at the University of Iowa and a teacher by trade, and “Sis” went out to Tacoma, Wash., where a cousin was serving, in hopes of getting a job at a defense plant.

Instead, they ended up teaching school. Both subsequently enlisted.

The WAVES were a branch of the U.S. Naval Reserves, proposed by Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox and authorized by Congress and President Franklin Roosevelt. Recognizing the need for personnel to fight the war, the women were to fill administrative posts to free up male sailors for sea duty. It would be decades before men and women served on warships at sea together.

“That was our jobs, taking a place and supporting people to go off and fight,” Costigan said.

Marge served in a procurement or purchasing position, acquiring surplus supplies from the Army that could be used by the Navy. “On my desk it had ‘Excess Material.’ And truer words we never spoken. That’s what I was” she said with a smile. “I was supposed to order from the Army excess materiel that they didn’t need that the Navy might use.”

Elizabeth “Sis” engaged in occupational therapy at military hospital in Bremerton, Wash., working with servicemen who were casualties with physical and psychological disabilities.

Marge also married during the war. Her husband, Clark Costigan, from nearby Elkport, was an Army major and an engineer who oversaw the construction of military airfields, from North Africa to the China-Burma-India theater. He could claim that he flew “over the Hump,” a dangerous but necessary aerial supply route over the Himalaya Mountains from India to China to support Chinese Nationalist forces and U.S. Army Air Force airmen based there. She and her husband visited many of the places where he had served in their later years. He passed away in 2004.

Marge was born in Elkader on Dec. 8, 1919. She went to school in Elkader and attended junior college there before graduating from Iowa, which she attended from 1939-41.

She was at Iowa at the same time as Heisman Trophy winning Hawkeye football player Nile Kinnick. “That was my claim to fame,” she said. “Nile Kinnick and I were in a class together. It was a class on airplanes. He became a pilot, and I worked on an air base.” Kinnick, a Navy ensign on the aircraft carrier USS Lexington, was killed in a training flight off the coast of Venezuela June 2, 1943.

During Kinnick’s Heisman season, Costigan recalled, “Iowa defeated Notre Dame and we didn’t have school on Monday. And the next week the defeated Minnesota and we didn’t have school on Monday.

“We were sitting waiting for a class to start,” and he opened the door and said. ‘What’s on for class today?’ And I said, ‘A test!’ He was gone a lot because he had a lot of honors” and was away receiving those. “He was very smart and very nice.”

After college, “I taught school for three years and went in the Navy, in the WAVES.”

She taught for two years in Northwood in north-central Iowa. Her third year as a teacher was spent in Tacoma. “My sister was a teacher too and we went out to visit my cousin Dick who was a P-38 (Lockheed Lightning fighter plane) pilot and the head of a squadron. Sis and I were going to work at a war plant. Which didn’t materialize; we taught school instead.

“We lived out there under grim circumstances with two wives of pilots, and one had a baby boy the night before (her husband) left for England,” Costigan said. “Some in the squadron we knew were killed. Another woman living there, whose husband was an intelligence officer, had a 13-year old girl.

“In this little house we had these three wives, my sister and I, a 13-year old girl, a black dog and a baby boy,” she said. “Two bedrooms. We lived like dormitory. No central heat. We chopped our own wood for a wood stove and a fireplace. And it rained most of the time.

“It was a tough year,” she said. “Not a deprivation, but a constant worry, of war.”

She and her sister both took tests for the WAVES and were admitted in the fall of 1944. “My mother had in her front window the little flag of four (blue) stars,” meaning she had four children in the service. “My mother didn’t tell us what to do, or my dad either. It was wartime. Everyone enlisted. That’s what everyone did.

Among the women services “The WACs were first,” the Women’s Army Corps. “They took the heat. They took a lot of heat and a lot of criticism,” Costigan said. “They went all over the world.”

After enlisting, she went to school at Hunter College in New York City — one of 95,000 women trained there over the course of the war for the Navy WAVES and counterpart Coast Guard SPARS. “It was great training,” she said.

“We did a lot of marching,” she said. “We had to march at least a mile to get to class.” On one occasion, she was told to lead the platoon in marching the following day. “I about fainted,” she said, “I had marched a lot, but I hadn’t paid much attention. Didn’t sleep all night. I thought ‘if you don’t say ‘halt,’ they might go right into a building. At first I was really scared, but then I had fun bossing them around. It ended up more fun than I thought it would be.”

She then went to Navy storekeeper’s school Milledgeville, Ga. “Which was a lot of math, which is not my thing,” she added. “The school was tougher in Milledgeville than in college (at Hunter), because it was math.”

She then pulled duty at an air base in Pasco, Wash. “I asked for Washington (state) thinking I’d get the coast. I got the desert.” Pasco is in southeastern Washington. “It was a fighter base. It was hot. Sandy. Sandstorms.”

She also spent some time at the U.S. government’s Hanford Site in Washington, where plutonium was produced for the first atomic bombs as part of the Manhattan Project.

“It was huge, vast buildings with barbed wire all around them, and nobody knew what they made of course” until after the war. “In World War II, you kept your mouth shut. Loose lips sink ships, you know, and everybody followed it.”

When an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, and then another on Nagasaki, “We didn’t discuss at that time whether they should have dropped it or not. We were extremely, extremely happy. Because the guys that has come back (to base) at the beginning of the summer were slated to go to Japan to fight. And they didn’t have to. So it was an extremely joyous day.”

Marge did avoid one brush with authority. She and Clark were married Sept. 30, 1945 and they honeymooned in Canada. She was risking being absent without leave. “The Navy frowns on being AWOL.” She told her new husband, “You’re a major, you call the WAVES. I was nothing but a lowly storekeeper. He called from Idaho to the head of the WAVES, and she said ‘You can have three more weeks.’ And then I had to be back. And I was out. Because they passed (an act) in Congress that all married WAVES would get out of the service.”

The couple both got out of service at about the same time and were home back in Elkader for Thanksgiving. “On Thanksgiving Day, brother Don walked in. Don had been in the service five years, which was an awful long time.” He’d served in the Third Armored Division in Europe and was in the Bulge, the last major German offensive of the war, in which 19,000 Americans lost their lives.

Marge didn’t see or hear much of her brothers during the war. “One didn’t think of too many hardships during the war, because everything in the paper was horrid. It was a constant worry.” A family might get a letter that a loved one had been lost in action months earlier. Several more distant relatives and friends were killed in the war.

“It was grim, you know? It was grim,” she said. “That was the worst part of the whole war. It was not the low pay, the deprivation, not being able to get gas, not being able to drive a car. The news on the war was grim.”

Brother Don, the father of former State Rep. Bill Witt of Cedar Falls, passed away in 1971 and William passed away in 1999. Marge’s husband prospered on construction and farming. Marge and “Sis,” lived next door to each other and were regular volunteers with the Clayton County Democratic Party and the Carter House Museum as well as the First Congregational Church. “Sis” passed away 2014.

“And here I am at 105!” Marge said. She still knits stocking hats for charity, has dabbled in poetry and gets in on a local bridge game on Tuesdays “except when it’s too cold.”

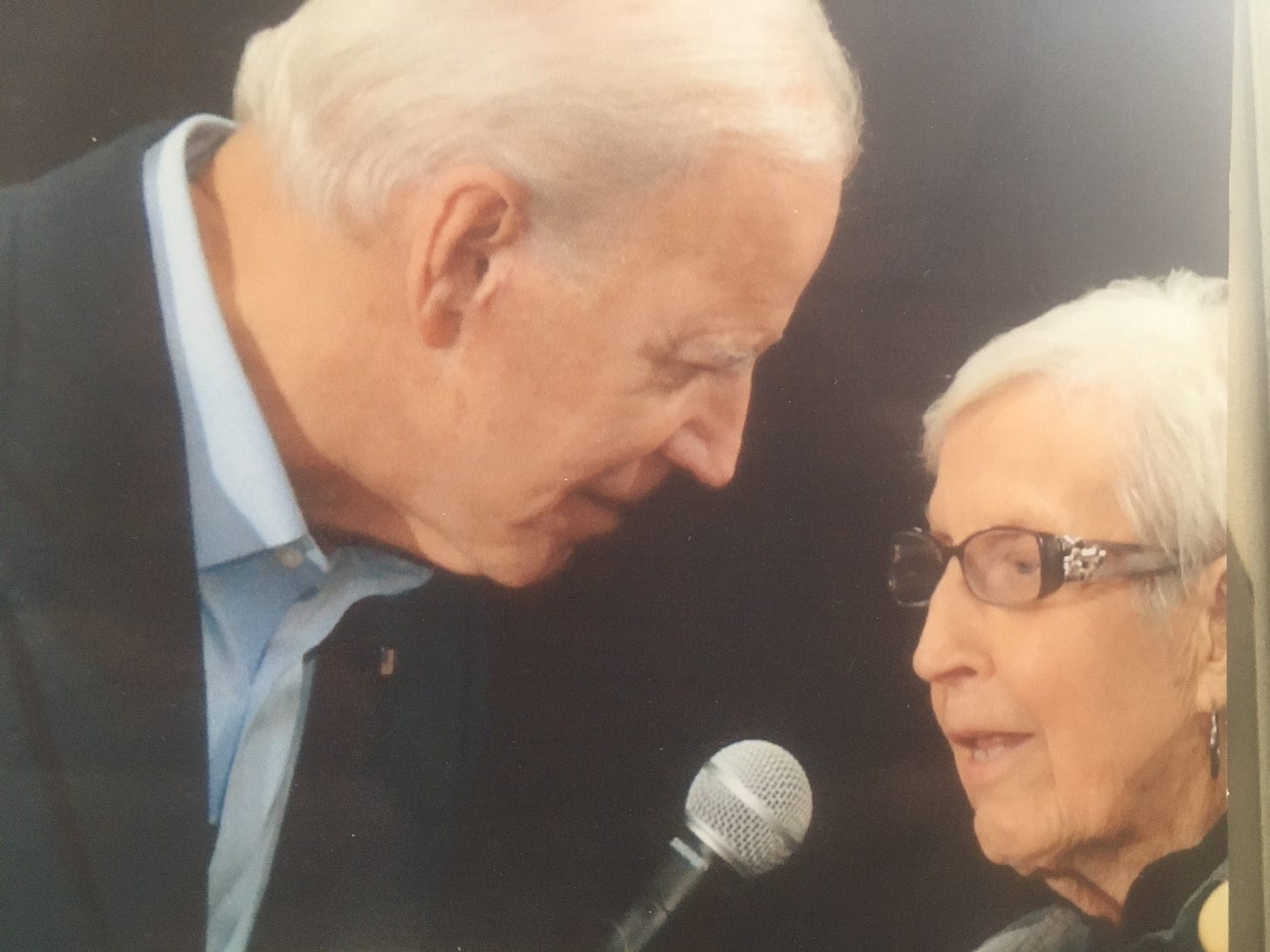

During a campaign appearance in Elkader in 2020, Joe Biden, then a former vice president, asked Marge what her secret was to her long life.

She said “Peanut butter and toast in the morning and a beer at night.”

Biden later sent her a case — of peanut butter.

“They said they thought it would be better than sending me the beer.” she joked,

Pat Kinney is a freelance writer and former longtime news staffer with the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier and, prior to that, several years at the Ames Tribune. He is currently an oral historian with the Grout Museum District in Waterloo. His “View from the Cedar Valley” column is part of “Iowa Writers Collaborative,” a collection of news and opinion writers from around the state who previously and currently work with a host of Iowa newspapers, news organizations and other publications. They are listed below. Clink on the links to check them out, subscribe for free - and, if you believe in the value of quality journalism, support this column and/or any of theirs with a paid subscription.

The Iowa Writers’ Collaborative

Great profile of an amazing woman! You obviously had a delightful visit with Marge. She is a real jewel! So much history in her still-sharp mind. Thanks for telling her story, Pat

Excellent!