Waterloo woman renews call for lasting memorial to early Black Boy Scouts

Edgar Cunningham was one of the first Black Eagle Scouts in the U.S.

WATERLOO — A young man in La Vista, Neb. has duplicated an achievement of his great grandfather nearly 100 years ago.

Chase Cunningham, the great grandson of Edgar Cunningham of Waterloo, has earned the designation of Eagle Scout.

His grandfather Edgar achieved it in 1926. He was one of the first Black youths in the U.S. to achieve Eagle Scout status. He was a member of the first all-Black Boy Scout troops in Waterloo and two of a handful around the state.

The 100th anniversary of Edgar Cunningham’s milestone will fall on June 8, 2026. That centennial and his great-grandson’s accomplishment underscores the need for a permanent memorial honoring Cunningham, his fellow Black Boy Scouts and their Scoutmaster, World War I veteran James Lincoln Page.

So says Carla McDonald, Edgar Cunningham’s granddaughter and Cass Cunningham’s second cousin. She has been campaigning locally for decades for some kind of lasting recognition or memorial to the Black Scout troops and her grandfather.

With the 100th anniversary of her grandfather’s Eagle honor a year away, McDonald reasons, there should be enough time to figure out something by then.

In April 1980, Edgar Cunningham’s son, longtime Waterloo educator Walter Cunningham, who became the first Black high school principal in Iowa in 1975 at his alma mater, Waterloo East High School, was presented with a special award in recognition of his father’s achievement — two months after his father’s passing. Scoutmaster Page, then 90, assisted in the presentation.

McDonald said that recognition was given at that time at the urging of longtime Waterloo civil rights activist Anna Mae Weems. McDonald feels recognition for the Black Scouts has been scant since then.

McDonald said she was “thrilled” at Chase’s Eagle Scout award. But she’s sad other members of the family “never got a chance to read about the Boy Scout troops or my grandad.”

She said she started her own research as a Black history project and is frustrated at the lack of recognition.

“I’d like to see them honored, a plaque to honor the troop and my grandad,” she said, placed in a appropriate location such as Walter Cunningham’s namesake elementary school, the Dr. Walter Cunningham School for Excellence in east Waterloo.

While the local Boy Scout council, the city of Waterloo and even former Gov. Tom Vilsack have presented McDonald with awards and proclamations over the years, McDonald would like to see a more permanent memorial honoring those early Black Scouts and possibly naming them, for posterity.

According to McDonald’s research, there were 32 all-Black Boy Scout troops nationally, and seven were from Iowa, including two troops in Waterloo which eventually consolidated. Others were formed within the Boy Scout councils based in Burlington, Davenport, Clinton and Des Moines.

Many were formed within the first 10 to 20 years after the Boy Scouts of America was established in 1910. It shows that Black Scouts and Scouting, and the opportunities provided minority youth, were a key part of the overall organization’s early history, McDonald notes.

The consolidated Waterloo Black Scout troop, Troop 12, conducted flag-bearing ceremonies to open the 1926 Scout-O-Rama at Waterloo West High School, according to Waterloo Courier files.

Many of the Black Waterloo Scouts went on to serve in ministry, labor and other fields, and influenced their offspring to do the same.

Their Scoutmaster, James Lincoln Page, was a native Kentuckian who came to Waterloo after the war and was the longtime maintenance engineer at the Paramount and Strand theaters downtown. He served as a sergeant in the all-Black Eighth Infantry of the Illinois National Guard, which became the U.S. Army’s 370th Infantry Regiment.

Page, a 28-year-old first sergeant with 10 years of experience in the Illinois Guard, apparently was assigned to a machine gun company as the 370th participated in a five-day assault on the heavily fortified German position of Mont de Signes. One of the regiment's platoons captured part of the German fortifications, turned the enemy's own guns on them and then held it for 36 hours without food or water until re-enforcements arrived.

One-fifth of Page's comrades in the 370th were killed or wounded in combat. A Victory Memorial to the Black soldiers of the Eighth Illinois National Guard who served in the 370th was erected in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the south side of Chicago in 1927, and was rededicated in 2019.

In a 1978 interview with this reporter during a reunion of his Scouts at his home on his birthday, Page said he applied his military experience from World War I to leading a Scout troop.

“A troop leader stays in the rear and makes sure everything is running smoothly,” he said. “I used to be the one to stay in the rear, make sure the fire was put out and that everything was okay.

”I never had a parent yell at me,” Page said with a laugh, “so I guess everything must have been okay!”

Cutting a piece of his birthday cake with a gold frosting star on it, the old Scoutmaster and Army first sergeant barked out. “Where’s Cunningham?”

The aging Eagle popped out of the scrum of his buddies, front and center to receive his cake.

“I always took a special interest in that boy,” Page said.

“Most of you are now fathers and grandfathers,” Page told his assembled Scouts. “I know you have carried your Scouting with you.”

At that celebration, Vivret “Vi” Norman, who worked with Page on the local Scouts executive council said, “Mr. Page has been inspiration to the community and to so many young men. He is revered.”

James Lincoln Page died in 1986 at age 96.

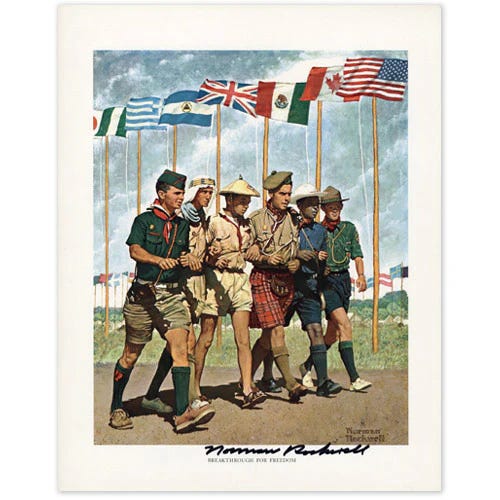

At the 1980 recognition for Black Eagle Scout Edgar Cunningham two months after his death, Scoutmaster Page presented Walter Cunningham with a print of Norman Rockwell’s Scouting portrait “Breakthrough for Freedom,” showing Scouts of many colors and nationalities.

Walter Cunningham passed away in 2000. But his son Benjamin Cunnigham bore that portrait to his son Chase’s Eagle Scout presentation.

Pat Kinney is a freelance writer and former longtime news staffer with the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier and, prior to that, several years at the Ames Tribune. He is currently an oral historian with the Grout Museum District in Waterloo. His “View from the Cedar Valley” column is part of “Iowa Writers Collaborative,” a collection of news and opinion writers from around the state who previously and currently work with a host of Iowa newspapers, news organizations and other publications. They are listed here. Clink on their individual links to check them out, subscribe for free - and, if you believe in the value of quality journalism, please support this column and/or any of theirs with a paid subscription. Thank you.

Great story and i love the "woke" print!