Advocate for racial, worker justice rose from Rath '48 strike tragedy in Waterloo

Waterloo's Russell Lasley rose to national prominence in meatpackers union, supported MLK

WATERLOO — This month marks the 75th anniversary of one of the most tragic and violent episodes in Waterloo's and Iowa's labor history.

But it started one local Black labor leader on a path to becoming a major figure in the American civil rights and social justice movements.

All hell broke loose at the Rath Packing Co. on the afternoon of May 19, 1948.

It resulted in one death, a riot and the dispatching of hundreds of Iowa National Guard troops to Waterloo to restore order.

Some 4,200 members of United Packinghouse Workers of America Local 46, known for its racially integrated membership and leadership, had been on strike at Rath --- then the city's largest employer --- for two months, as part of an industry- wide strike involving several U.S. packinghouses.

Workers were seeking a 29-cent hourly raise. They’d been offered nine cents. They were making less than $1 an hour.

Union members striking at Rath were especially angry when they saw the strikebreakers --- "scabs," they called them -- coming to cross the picket line and report for second-shift work that afternoon.

One of them was 55-year-old Fred Lee Roberts, a Black farmer who lived near Dunkerton. He had 15 children and needed the money.

Roberts had a gun --- a World War I .45 caliber pistol. And on that day, he used it.

After being turned away at one gate where primarily Black picketers were located, Roberts headed for the main gate. Another group of strikers jumped on Roberts's car and started rocking it, trying to get him to turn back. He shot and killed one of them, William "Chuck" Farrell, who had jumped on the car's running board and was part-way through the window.

Fellow picketer Jim Hamlyn Sr., who had climbed on the opposite side of the car from Farrell, said in a 1998 Courier interview that Roberts had shot Farrell through the cheekbone and “he was dead before he hit the ground.” The bullet passed through Farrell's head and struck bystander Margaret Draheim in the shoulder. She was hospitalized but survived.

Waterloo police officer Charlie Rehorst jumped on Roberts's car, ordered him to drive away from the scene and disarmed and took him into custody without incident. But the strikers, angered over Farrell's death, snapped, overturning cars and setting spilled gasoline on fire.

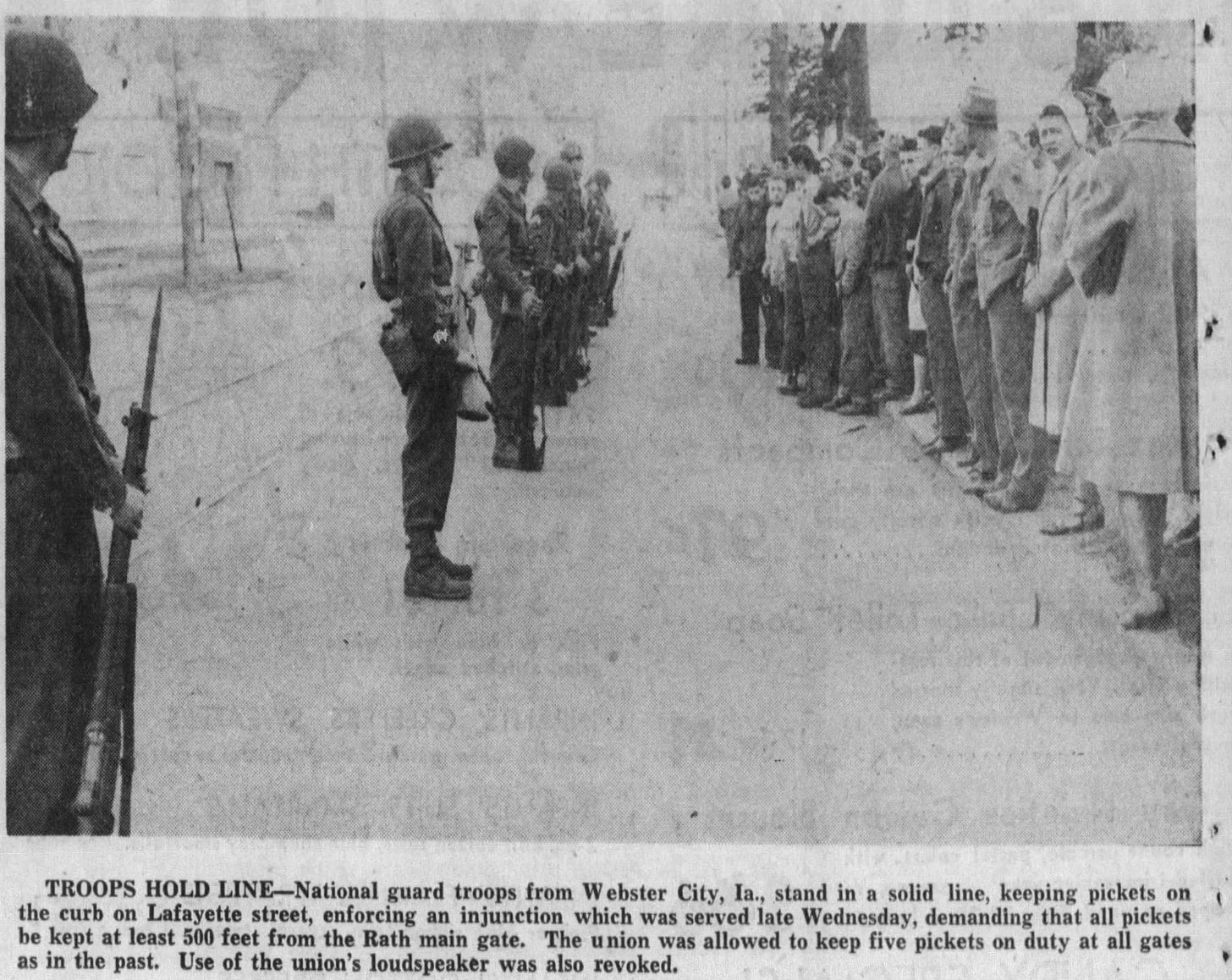

Local authorities contacted Iowa Gov. Robert Blue, who dispatched more than 800 National Guardsmen from 16 cities including Waterloo --- one fifth of the state's contingent --- to restore order. The strike was crushed and the union accepted the nine-cent hourly raise.

A grand jury investigated. A trial jury found Roberts innocent of manslaughter, deeming it either an accident or self-defense. Some union officials were fined and one was sentenced to 60 days in prison. They were pardoned by Iowa Gov. Herschel Loveless in 1960.

But it was shortly after the strike that one of its local organizers, Russell R. Lasley, rose to national prominence within the UPWA and played a major role in the national civil rights movement.

Lasley was one of several union officials criminally charged with conspiracy in the strike and riot. He was ultimately fined $500 on a lesser contempt of court charge in 1951.

Less than a month after the strike, Lasley, also a 1948 candidate for Iowa lieutenant governor on former Vice President Henry Wallace's Progressive Party ticket, was elected vice president with the UPWA international union that June in Chicago. Lasley moved there, resigning from the Progressive ticket.

It was at that point that the UPWA and Lasley became nationally involved in civil rights. The union began pursuing anti-discrimination activities in 1949 and formed an anti-discrimination department in 1950, which Lasley headed.

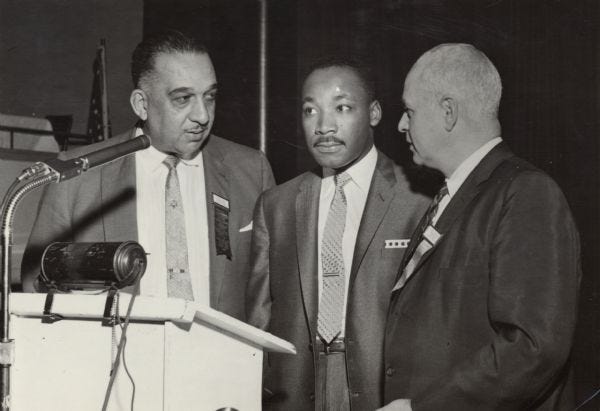

Lasley also brought the power of his union to bear to create one of the driving forces of the American civil rights movement --- the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

"I guess the Southern Christian Leadership Conference would not have existed without the Packinghouse Workers union," King scholar Clayborne Carson, professor of history and director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University in California, said in a 2013 Courier interview.

Lasley participated in the organizational meeting of the SCLC in January 1957 and served on its board of directors.

"I am sure the union provided the majority of the SCLC's budget when it first was established," said Carson, who was selected by Coretta Scott King in 1985 to edit and publish her late husband's papers.

Lasley was "one of my heroes," said the late Lyle Taylor, who president of the UPWA's successor union local at Rath.

Despite his substantial role on the national labor and civil rights scenes, Lasley never forgot his Waterloo roots. He was a guiding force in contract negotiations and other labor matters at Rath.

At national conferences, "We'd always meet with him because he was from our local originally," Taylor said. "He was a quiet, but very stern man, and when he spoke you knew it was fact," Taylor said. "He was also very reasonable, and when we came to meet with the company, he'd figure out a way to resolve issues."

"What a jewel," said Anna Mae Weems, longtime Waterloo civil rights activist, said of Lasley in 2013. Like many local Waterloo civil rights leaders, Weems got her start through the union local at Rath.

Lasley, Weems recalled, "was a big, tall man, light complected, and had big hands. He'd slam his hand down on the table when making a point. We'd say, 'Don't break the table!" She also recalled he worked with the company to improve the flow of the meat-cutting operation on the shop floor.

By the time Lasley passed away in 1989, Rath had liquidated in bankruptcy and his union had merged with another.

One has to look closely to find Lasley's footprints in the sands of history today. But they are there, and they are substantial.

The Iowa Writers’ Collaborative

Great story. I was not familiar with him.