'Thank your for your service' a long time coming for Greene Vietnam vet

Greene's Tom Johnson feels relief, appreciation after telling his story.

GREENE - Tom Johnson left a widowed mother to serve in Vietnam in 1969.

When he returned after two years in combat 8,500 miles from home, his reception was a cold shoulder from a staff of eight flight attendants on a half empty plane home. He was the only passenger wearing a uniform.

During those two years, Johnson endured grueling training by brutally demanding drill instructors, followed by time in Vietnam working 12-hour shifts in an artillery fire direction center, drawing up fire missions on two minutes’ notice.

The duty shifts were interspersed by 12 hours on guard, armed with an M16 automatic rifle and watching for infiltrating enemy, snatching bits of sleep whenever possible. Supply truck runs frequently turned into ambushes. "I'd ride in the back with a machine gun, an M16, for protection," he said.

When soldiers picked up word of an imminent attack, they laid down covering fire around a 500-foot perimeter from their positions, like someone might water a lawn.

After he got home, younger family members asked him, “ 'Did you kill anyone?' ”

"I said no," he said. "I couldn't tell them the truth."

When he wouldn’t talk about it, family members encouraged him to write about it.

He did. It took him several years, but the experience was cathartic.

Now, he wants people to learn and remember what he and his comrades endured.

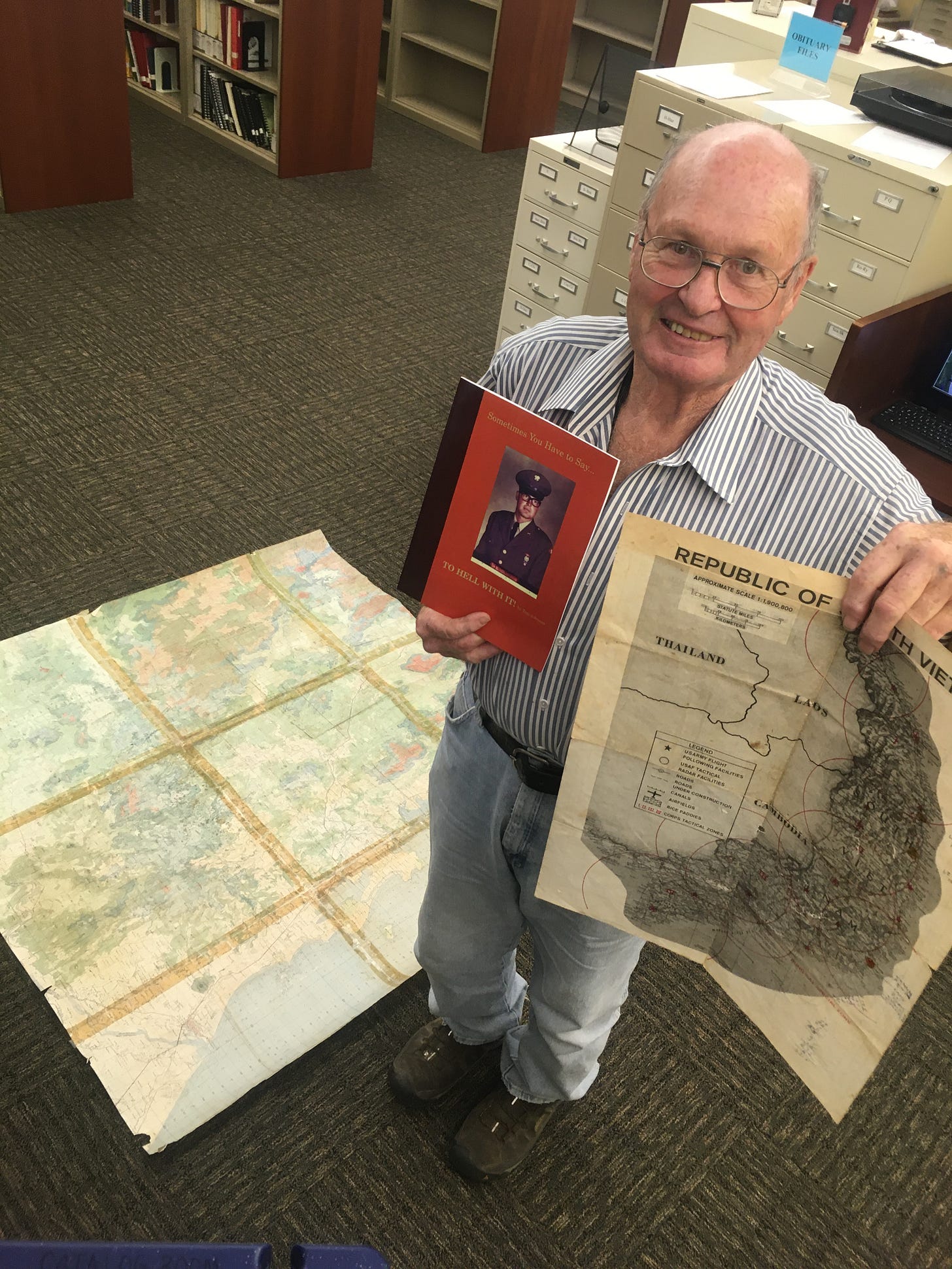

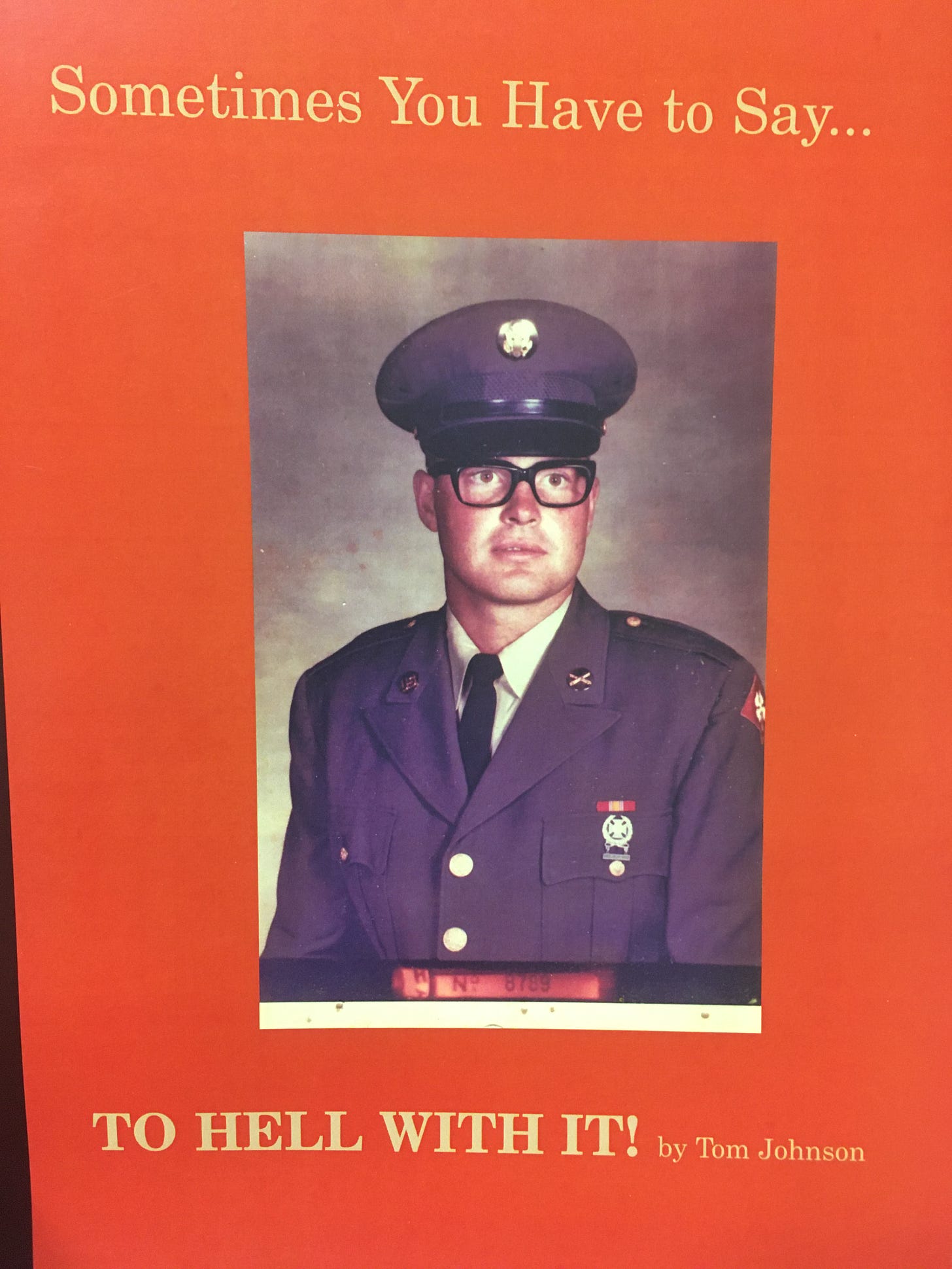

He put his words and images into a book bluntly titled “Sometimes You Have to Say, ‘To Hell With It!’ “ He distributes it himself. It’s been popular enough that he has had to get additional copies printed. He’s also provided an oral history and artifacts to the Sullivan Brothers Iowa Veterans Museum in Waterloo.

He was a little sheepish about the book’s title at first, but when he showed it to a now-deceased local pastor -- Msgr. Walter Brunkan, pastor at St. Mary's Catholic Church in Greene and the former longtime principal of Waterloo Columbus High School -- Brunkan said, "I've heard worse."

In truth, Johnson had seen worse in Vietnam. A lot worse.

He got his draft notice shortly after graduating from Greene High School in 1967, but received an 18-month deferment while attending technical college in Minneapolis. Then he received another draft notice. "I talked to my mom and I said, 'If they want me that bad, I'm going,' " he said.

His father had gotten out of farming and had just gotten into real estate when he died of a heart attack at age 51. "I was worried about my mother. She went along with it. I said I should do it. It wasn't easy for anybody."

He received training at Fort Polk, La. in steamy August. "That was hell, mainly because of weather. That was an infantry fort. They trained us to go to Vietnam," he said. "All of those drill sergeants were Vietnam veterans or Korea veterans or World War II veterans. They all knew we were just farm boys or guys from the city. We didn't know anything about killing people. And we were going up against people who had been fighting for decades. They knew we had to be tough because once we got there, it was deadly. Most of the guys killed, were killed in first two or three weeks they were there."

From Fort Polk, he went to Fort Sill, Okla. for artillery training. After 10 days at home on leave, he was shipped off to Vietnam.

In tests, he'd shown aptitude for various kinds of duty, including officer training, Army Ranger school and special forces. But several of them would have required an additional, third year of service.

"Being brutalized by drill sergeants -- and that was their job -- it was extremely tough and extremely hard, and I wanted to get out. I didn't want another year," he said. He settled on artillery, training on the 105mm howitzer.

Johnson served in Battery A. of the 7th Battalion, 15th Field Artillery Regiment of the U.S. Army's 1st Field Force.

"I got to Vietnam on Christmas Day of '69, and the first sergeant says to me, 'You're going to a fire direction center.’ I didn't know what it meant."

It involved plotting coordinates for fire missions. and coordinating fire .

"It was a little safer. I wasn't on a (gun) battery,” he said. “We had four guns. The gun crews took care of the guns. We would determine which gun would fire and figure out the coordinates for that. I had no clue how to do any of that. But most of the people in fire direction centers were four-year college degree people or higher; they were smart people. They knew they had someone they had to get trained, so they worked on me very hard.

"We always had a double check; two guys would figure out the same fire mission,” Johnson said. “We had two minutes or less. Once we got a call, we had two minutes to get a round in the air. We had to be fast, and we had to be accurate. A lot of times we were firing with (friendly) troops on the ground. When you're dropping high explosive (shells), you want to be right,” If not, he said, “they're gonna die."

Initially based at a landing zone in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam, they moved south to positions in the Mekong Delta in support of South Korean allied troops. Then the were moved back north, to Landing Zone Blackhawk, or “LZ Blackhawk,” situated close to what was known as " The Triangle," where the borders of South Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos met. It was near the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a main supply route for the opposing North Vietnamese Army.

"It was like an Interstate 35, but you couldn't see it. It was hidden in the jungle," he said.

He spent the bulk of his 15 months in Vietnam there. "The last few months, we would take two of the guns and go up to the Triangle. We would sit about 1,000 meters off the border -- we were not allowed to go in — and we'd fire on that Ho Chi Minh Trail for three or four days. We could shoot 18 miles but we had to be careful. We would have a company of tanks and a company of South Vietnamese soldiers with us for protection. We'd stay there for three or four days, and hurry up and get out of there before we got caught.”

They were subject to attack from ground forces. "At LZ Blackhawk we had concertina wire all the way around us. There were several layers of that. And mixed with them were trip flares, mines, various traps and machine guns in guard towers," he said.

In the event they were overrun, a sergeant was assigned to drop an incendiary grenade down a gun and destroy it rather than have it be captured intact.

Enemy troops - which included men, women and children - would try to get through the wire, Johnson said, and he and his comrades would be subject to mortar and rocket attacks.

They were near an air and Army base at Pleiku and received air support from fighter jets, attack helicopters and fixed-wing propeller- driven AC-47 gunships -- converted World War II C-47 transport planes known as "Puff the Magic Dragon."

If forces were aware an enemy attack might be imminent, adjacent artillery batteries would shell the area around Johnson's LZ, "and we would do the same for them."

Asked if enemy ground troops ever made it through to Johnson and his comrades, he said, “They tried. They didn't make it." But Vietnamese civilians in camp cleaning or doing other chores for the soliders may or may not have been hostile and scouting the installation. The individual soldiers always had M-16 assault rifles at the ready. even in the fire direction center as they ploted fire missions.

"We had two crews in the fire direction center," he said. "We worked 12-hour days, seven days a week, night shift or day shift. If you were off duty and we had incoming mortar rounds, it was the duty of the off-duty people to protect the people who wore working. You would station yourself at the entrance, front and the back (of the fire direction center), maybe sit on the roof, to protect the people inside. A friend of mine from Chicago, he and I manned and 82 mm mortar. And if we had incoming rounds (at night) we'd run out to that mortar and shoot illumination rounds" to reveal the enemy’s position so Johnson and his buddies could return fire.

As far as sleep was concerned, “you sleep standing up, you sleep when you could. You may go days," he said

LZ Blackhawk was so disruptive of enemy traffic on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, Johnson said, that the unit picked up radio traffic and intelligence that the North Vietnamese had targeted them for attack during the Vienamese Tet holiday of 1971.

"They were so upset at us," he said. "We took it as a real threat. We were on red alert for three days. Nobody slept. You had all your gear, you had your M16s. If you were off duty, you guarded the building. And we were constantly firing. We had quad-.50s (machine gun batteries), several .50 caliber machine guns; we had guard towers.

”Those guys were constantly shooting,” Johnson said of his comrades. “We had a 500 meter free-fire zone on three sides. The other side was a (friendly) montagnard village. For three days, we did nothing but shoot. We didn't know if we hit anything, but if there were dead bodies out there, that was too bad." The idea was to put down enough fire to ward the enemy away; no one complained about whether it was a waste of ammunition.

"We took it serious. Everybody else took it serious," he said.

Montagnards "were peaceful people; most of them were farmers. Very primitive. They were good people. South Vietnamese, you never knew." Some were hostile Viet Cong guerrillas or North Vietnamese.

"Some of them were kids," he added. "You could be 10 or 12 years old and be full-blown soldier." The enemy was also hard to fight because of the deep network of underground tunnels they could take refuge in.

"We had two girls we knew were on the base at certain periods of time. We found them in the wire one night," dead, trying to get through. "They were North Vietnamese troops. They had uniforms on, so I would say they were (NVA) regulars."

When he rode shotgun with an M16 on the back of a truck on supply runs, there was direct contact with the enemy in ambushes.

"I had one time I was laying on a bunch of boxes in a deuce and a half (truck) with an M16 across my chest. A VC opened fire. It rattled right underneath me; sprayed, He thought I was standing up. Well I wasn't. I was laying down," on the boxes and above the enemy’s field of fire. Otherwise, "he would have got me. I got him. He shot the heck out of the truck. But I was a better shot."

He left LZ Blackhawk in March 1971, near the end of his hitch. He volunteered to go on another mission close to the trail near the end of his time. but his commanding officer said no. "I only had two weeks in country left. He said 'You've done your time.,' " Johnson said.

Within a couple of days of leaving LZ Blackhawk, he was on a flight to Guam and then to Fort Lewis, Wash. where he was mustered out.

"I had enough money for a plane ticket to go to Minneapolis," he said. "It should have been a joyful trip but it was miserable. The plane was half full and there were six to eight stewardesses on that plane. They wouldn't talk to me. They didn't offer pop or lunch or booze, anything. They wouldn't talk to me at all. "

He was in for a shock to his system when he got to Minneapolis, "It was great to be home, but damn, it was cold!" he said — especially coming out of tropical weather in Vietnam.

"You're used to 110 degrees. the hottest it got was 126. Vietnam was hot, dirty, humid. Just flat-out ugly. The highlands were better because of the vegetation." And then everything would be saturated or flooded during monsoon season. "if it rained too hard we couldn't fire our guns" lest the shells, which detonated on impact, exploded upon exiting the muzzle.

When he returned to Greene he discovered nearly half the boys in his graduating class had been to Vietnam, and more from other classes. "Guys that had been to Vietnam and come back, plus my classmates. the townspeople, were warm” and welcoming. ”You didn't have the problems the bigger communities had" with indifference or hostility to returning veterans.

He also found some friends didn't come back. Many died later or are suffering from service-related illnesses. "Agent Orange, heart disease, strokes -- all service related," he said.

Of those who didn’t come back, he said, "We all took a chance being there. it's just the luck of the draw. There's no rhyme or reason. If you were infantry or artillery, your chances of getting shot were greater, but there's no guarantee if you were running a typewriter you would get it -- like when they invaded Saigon during the '68 Tet (offensive)," he said. "There was no place that was really safe."

And with the number of troops rotating in and out, one guarded against getting too close to anyone, particularly new troops. "because they might not make it."

After returning home, Johnson eventually made a career at Sukup Manufacturing in Sheffield where he worked for more than 30 years.

Reflecting back on his service, he said, "For decades you didn't talk much about it. Once in while you'd get together with one of your ex buddies, drink some whiskey and start telling some stories. Other than that, you never talked about it.

"Was it (the war) right or wrong? You didn't have a choice,” he said. “You had to defend yourself, defend your country, what you thought was right. Until all of a sudden they pulled everybody out and you feel sorry for the people you left behind, as far as the South Vietnamese soldiers. Like the interpreter we had; what happened to him? We won battles. We did not win a war."

Johnson has three sons and a daughter. “They said ‘We know you don't like to talk about it. Why don't you write about it?’ " while he was healthy. "That's why I wrote it (the book)-- for the kids to know."

He also has worked with staff of U.S. Sen. Charles Grassley's office to get medals due him. He was injured when an enemy mortar round went off near him, jarring him into dropping a shell he was carrying on his foot and injuring his back He has never received a Purple Heart.

He's currently struggling with a heart condition stemming from exposure to the toxic defoliant Agent Orange during his service.

It's a consolation now, he said, that there's more acceptance and appreciation for veterans in general and Vietnam veterans specifically.

"I've had a lot of people in the last 10 years that have come up to me and thanked me for my service," Johnson said. "One lady said 'I suppose you get tired of hearing it, but thank you for your service,' I said 'I never get tired of it.'

”Whenever somebody tells me that, a little bit of that darkness, a little bit of that hate, comes out," and dissipates, he said, like infection from a wound. "It's a little refresher. It's been a long time coming, but it's a nice relief."

Johnson says anyone interested in a copy of his book may contact him at tomjohnsonativyave@gmail.com or at (641) 816 4547 or (641) 330 2714.

Pat Kinney is a freelance writer and former longtime news staffer with the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier and, prior to that, several years at the Ames Tribune. He is currently an oral historian with the Grout Museum District in Waterloo. His “View from the Cedar Valley” column is part of “Iowa Writers Collaborative,” a collection of news and opinion writers from around the state who previously and currently work with a host of Iowa newspapers, news organizations and other publications. They are listed below; clink on the lings to check them out, subscribe for free - or support this column and/or any of theirsS with a paid subscription .

The Iowa Writers’ Collaborative

Thanks for this feature, Pat.

Great read, Pat. I’m old enough to have had a lottery number but was just young enough to have Nixon end the draft before my number came up. I have no idea what I would have done. I certainly had no interest in going to fight that particular war. Tom’s story makes me feel quite lucky to have missed it.