Playing for the man

Waterloo community leader and Hawkeye football standout Robert Smith says his coach was about more than Xs and Os.

This is about a Black man, a white man, and a community.

The Black man is Robert L. Smith Jr. The white man is Hayden Fry. And the community is Waterloo.

Smith has done a lot for Waterloo over past 30-plus years. He's been president of the school board, chaired the Black Hawk County Board of Supervisors and he's now director of the University of Northern Iowa Center for Urban Education (UNI-CUE) downtown, providing educational opportunities to disadvantaged youth. He's a member of President Mark Nook's cabinet at UNI. He's also a high school basketball and Division I NCAA football referee - in fact, he’s helped officiate bowl and national championship games.

He's co-chaired the local Cedar Valley United Way campaign and served on the board of a local bank. He's hosted a local radio show on financial literacy and serves on a new local committee working to uplift and empower Waterloo's Black community - including being part of an investment club. And he’s been an academic advisor for the Big Ten collegiate athletic conference.

But he wouldn't have done what he did in Waterloo, or in Iowa, without Hayden Fry. In fact, Smith said, ”I wouldn’t even be in Iowa. Wouldn’t be married 34 years. Wouldn’t be where I am today.”

And it was all because of something Fry did about two decades earlier.

Smith grew up in Dallas, Texas, the son of a retired custodian, a single mother. He showed talent in football -- in a state where football is a religion and college teams abound. And football is just as big across the border in Oklahoma.

When time came for college he had his pick of schools -- including the University of Texas and the University of Oklahoma.

That's when Hayden Fry came into Smith's life -- a fellow Texan, but a white man who coached a college team 800 miles away, and up north in the cold - at the University of Iowa, in a predominantly white state.

Smith rapidly found out Fry was about more than football.

"I tell people that was my introduction to diversity, equity and inclusion," said Smith.

"That really shaped my way of thinking about race. I didn't understand it at the time, but it shaped me.” Fry sat with Smith and his mother Gertrude at their home. “We really had some heart to heart conversations. And he didn't shy away from talking about race, what was going on back then, and he put me at ease. Mom and I just trusted him."

As a young man in a Black neighborhood, Smith said, the sentiment was that white people, for the most part, were to be avoided, or at best, tolerated, based on experience. While he had white classmates, a major part of the neighborhood encounters with white adults involved police — which usually meant something bad had happened or was about to happen.

But Fry eased Smith's and his mother’s minds not just from what he said, but what he had done.

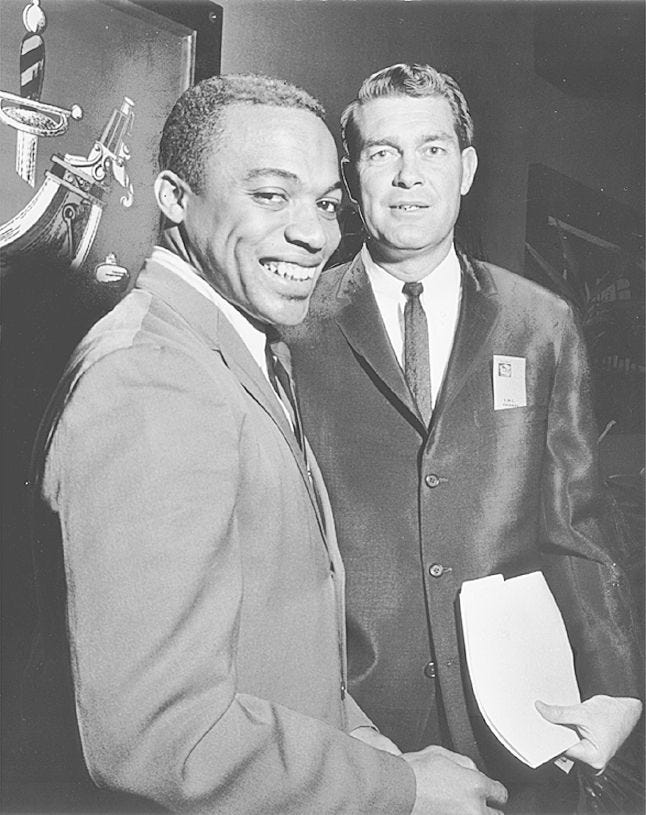

In 1965, as head football coach at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Fry offered a scholarship to another young Black man, Jerry LeVias. It was the first scholarship offered to a Black athlete in the Southwest Conference, which included almost all the large universities in Texas.

Fry and LeVias were to the Southwest Conference what Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson were to big-league baseball. There was backlash against both men.

But their courage wasn't lost on Smith's neighbors or family.

"Here was a white Southern gentleman who did something around the year I was born. You could see the level of respect older Black people had for what he had done when he gave Jerry LeVias a scholarship. I had older Black family members who talked highly of Hayden Fry.”

There were big local schools and big-time coaches nearby. Barry Switzer at Oklahoma. Fred Akers at Texas. It was decision time.

"My mom said, 'Do you want to play for the institution, or do you want to play for the man?"

Smith chose the man. He was Fry's first recruit from Texas at Iowa.

”I wouldn’t be where I am today if he hadn’t done what he did in 1964-65” with LeVias, Smith said. “I certainly wouldn’t have come to Iowa for any other reason. He just thought it was right. He wanted people who deserved an opportuity to have an opportunity.” Smith agreed that Fry’s Marine Corps service helped shape his convictions.

”You knew he was just sincere about it,” Smith said. “We had those conversations with my mom. She just knew - ‘This guy’s real, he’s not pretending.’

"It was more to me than just playing football," Smith said. "I respected and trusted the guidance I got from Coach Fry."

But play football he did. Smith was part of the Hawkeyes' 1985-86 Rose Bowl squad that was for a time ranked No. 1 in the nation. A years later, as a senior, Smith caught a crucial two-point conversion in a Holiday Bowl shootout with San Diego State that the Hawkeyes won 39-38. He still ranks among the top receivers in school history.

Iowa City was where Smith also met his wife Terri, who was from Waterloo, where they would make their home -- and where Smith would have as much impact as Jerry LeVias himself did in Houston, where he played professionally for the Houston Oilers after college. LeVias went into private business and worked for many years awith youth and as an ambassador for the NFL’s Houston Texans.

Fry died in December 2019, two months shy of his 91st birthday. But for Smith, his coach’s example endures. While Smith has encountered racism, including "driving while black" and in more subtle ways, he tries to convey the lesson he learned from Coach Fry — to evaluate each person on their own merits. When racism occurs, he said, "see it for what it is and don't paint everybody with the same brush."

“I walked away from that relationship (with Fry) understanding, there are bad people and there are good people. They’re in all races.” He’s taught his kids, “Find the sincere ones, and you’ve got a chance. Stay away from the bad ones as best you can.”

It's a lesson he's tried to impart on people regardless of color, and he's made people reconsider their thinking - whether speaking to audiences or one person at a time, in individual conversation.

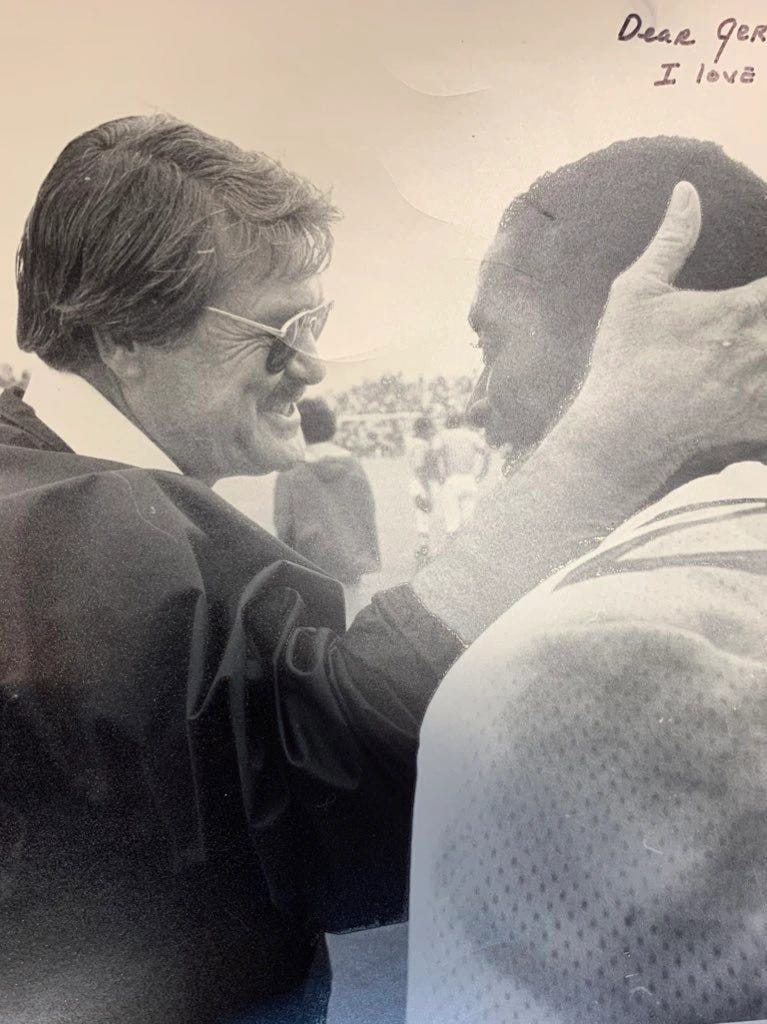

Smith recalls receiving a photo from Fry of himself and the coach on the sideline, on which Fry wrote to him, "The players, coaches and staff are very happy you came to Iowa. We love you."

“He didn’t have to do that,” Smith said. “I never had a white man say ‘I love you.’ There was nothing to gain doing that. But he was sincere.”

He sent the same photo to Smith’s mother, and wrote, "Dear Gertrude - I love Robert too."

Iowa Writers’ Collaborative Columnists

Laura Belin: Iowa Politics with Laura Belin, Windsor Heights

Doug Burns: The Iowa Mercury, Carroll

Dave Busiek: Dave Busiek on Media, Des Moines

Art Cullen: Art Cullen’s Notebook, Storm Lake

Suzanna de Baca Dispatches from the Heartland, Huxley

Debra Engle: A Whole New World, Madison County

Julie Gammack: Julie Gammack’s Iowa Potluck, Des Moines and Okoboji

Joe Geha: Fern and Joe, Ames

Jody Gifford: Benign Inspiration, West Des Moines

Nik Heftman, The Seven Times, Iowa and California

Beth Hoffman: In the Dirt, Lovilla

Dana James: New Black Iowa, Des Moines

Pat Kinney: View from Cedar Valley, Waterloo

Fern Kupfer: Fern and Joe, Ames

Robert Leonard: Deep Midwest: Politics and Culture, Bussey

Tar Macias: Hola Iowa, Iowa

Kurt Meyer, Showing Up, St. Ansgar

Kyle Munson, Kyle Munson’s Main Street, Des Moines

Jane Nguyen, The Asian Iowan, West Des Moines

John Naughton: My Life, in Color, Des Moines

Chuck Offenburger: Iowa Boy Chuck Offenburger, Jefferson and Des Moines

Barry Piatt: Piatt on Political Behind the Curtain, Washington, D.C.

Macy Spensley, The Creative Midwesterner, Davenport/Des Moines

Mary Swander: Mary Swander’s Buggy Land, Kalona

Mary Swander: Mary Swander’s Emerging Voices, Kalona

Cheryl Tevis: Unfinished Business, Boone County

Ed Tibbetts: Along the Mississippi, Davenport

Teresa Zilk: Talking Good, Des Moines

To receive a weekly roundup of all Iowa Writers’ Collaborative columnists, sign up here (free): ROUNDUP COLUMN

We are proud to have an alliance with Iowa Capital Dispatch.