New Waterloo grocery is doing it the 'Wright' way

First Waterloo downtown grocery in decades honors, fulfills dream of longtime council member

WATERLOO — Willie Mae Wright asked for something her neighborhood hadn’t seen in 20 years.

That was 30 years ago.

Now, the veteran former City Council member is seeing her dream come true — and her name’s on it.

On Tuesday, All-in Grocers opened up just across the street from Wright’s home — and the 28,000 square foot, $10.2 million grocery has a local meeting space and community center named for her. She served on the council 10 years in the 1980s and early ‘90s.

Wright indicated she was stunned when she saw her name on the store marquee while on her way home from a medical appointment.

“I said ‘My name’s on this thing! Let’s see what they have in here!’

”I did have a person contact me about employment” there, she said. because her name’s on the building.

It’s the first full grocery store in the neighborhood in 50 years. Wright’s son Alvin, a recently retired Waterloo teacher, worked at the old Del Farm store in the 700 block of East Fourth Street prior to graduating from East High School in 1971. It closed a few years thereafter.

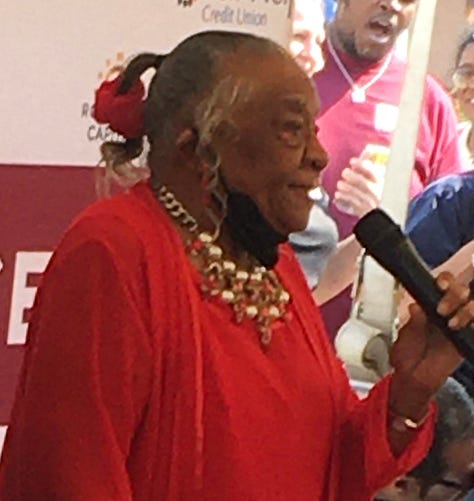

“Today is a great day. Thank you! Thank you!” a breathless, emotional Wright, who turned 91 April 9, told the assembly of 300 to 400 people.

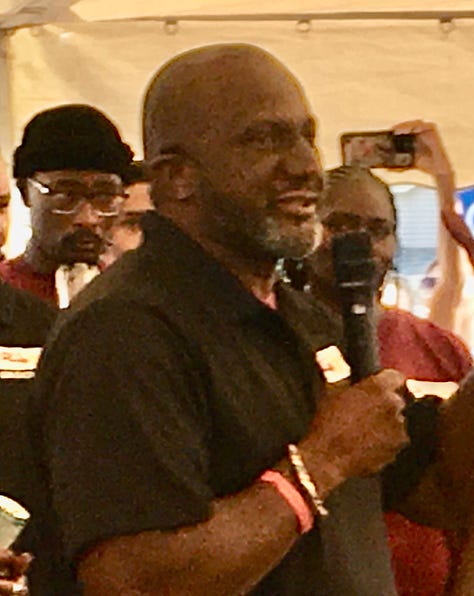

All-In Grocers is a dream of founder Rodney Anderson, who grew up down the street from Wright, and business partner Lance Dunn. It has been been five to seven years in the making, slowed by the pandemic and subsequent issues with cost increases, financing and site complications. But it’s finally happened.

”Thank you so much Rodney. I can’t thank you enough for this project. God bless you,” Wright told Anderson.

”I thank God for Rodney Anderson, Lance Dunn,” said Waterloo Mayor Quentin Hart. “They could have easily taken their money and their resources and headed out somewhere else.” But, the mayor said, they decided to invest in their home community despite reports like the financial website 24/7 Wall Street rating Waterloo as one of the worst places in the nation for Black people to live.

”They said, ‘We hear what the report says. But we’re not going to allow the report to dictate how great and how good our community can be defined now.’ ” Hart said.

Waterloo native and Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones has, with high school friends Joy Sallis Briscoe, Sharina Sallis and Lorrie Dale, established the 1619 Freedom School, an after-school youth literacy program which will have a location in the store building.

“I knew this was going to be an emotional moment. I can’t even look at Rodney right now,” said Hannah-Jones, author of The 1619 Project. “I was born and raised right in this neighborhood. I also know we never had a grocery like this serving our community… This is a man who is about his community and serves his community.” Her mother still lives in the neighborhood.

”White folks don’t have to celebrate a grocery store going in their community the way we do,” said Hannah-Jones, who is now the Knight Chair in Race and Journalism at Howard University in Washington, D.C. “We face such obstacles to do things every other community can do.

”There are powerful people in this community who did not want this place to exist,” Hannah-Jones said. “But Rodney and Lance Dunn had to fight every day to create this space for our community. And that fight, I was honored to support.”

Noting the institutional racism many of Waterloo’s Black ancestors had to face and overcome when they came to town during the Great Migration from the South, Hannah Jones said, “We are doing for ours and ourselves. Let this All-In Grocers, in a redlined neighborhood, a food desert, a predominantly Black neighborhood, be a shining symbol of their hopes and determination, and ours.

”I ask each of you, in the spirit of our ancestors, to protect this place,” she said — and protect it for those who will work, learn and receive a second chance because of the store and the service it will provide the community.

The 28,000-square-foot grocery store development includes a restaurant, laundry, Wright’s namesake community center, after-school program satellite office and reentry services and carry fresh affordable food. Anderson estimated the grocery portion of the development has about 24,500 square of space. The store employs about 60 people. It is also adjacent to a CVS Pharmacy which opened about 10 years ago.

Several project supporters said the development could be come a pattern for similar projects around the country.

Anderson had announced before the City Council, with Wright in attendance, that a meeting area in the building would be named for her.

“I about fell on the floor,” she said.

“It’s beyond my imagination,” to have her name on the building, she said, but she knew the need was there.

”When I was on City Council in the ‘80s, when the downtown went down, and we were wondering what to do. And I said, ‘Bring a grocery store. And people will come.’ “

It was during the depths of the 1980s recession and farm crisis. Rath Packing Co., once the city’s largest employer, had just closed for good after 90 years in business. John Deere laid off 9,000 workers — almost 60 percent of its Waterloo workforce — and most of those who remained had been on strike or were locked out for five months. The popular saying in town was “Last one to leave, turn out the lights” and the “For Sale” signs outnumbere the yard signs in the municipal election.

Wright said it didn’t have to be that way.

She was the senior member of the City Council, beginning her third term. She also was only the second Black person in the city’s history to serve on the council. None of her peers had more than two years in office, including the mayor at that time, Bernie McKinley.

She said downtown Waterloo and the surrounding east-side neighborhood in the Fourth Ward which she represented on the City Council, would support a grocery store.

Hardly anyone listened.

”Their reasoning was there was no parking for a grocery store,” Wright said. “But I told them if they bring a grocery store, people will come. Because they have to buy groceries.”

In the intervening years, she saw homes and churches demolished across the street from her home, parallelling Franklin Street, once part of U.S. Highway 20. The thoroughfare, just across from downtown became an economic barrier.

Then, in 2015, one of Wright’s successors as Fourth Ward council member, Quentin Hart then already in his seventh year on the council, was elected mayor of Waterloo — the city’s first Black mayor.

”Mayor Hart promised me he was going to get that area developed,” Wright said. Turning to the mayor during her remarks, she said, “You kept your promise.”

Anderson said he intends for his store to be responsive to the needs of the community.

”Black, white, we have to band together,” he said. “Come to us with suggestions. But understand, it was 50 years before we got here.” Pointing to the diverse staff behind him, he said, “We look like Waterloo.

”I love this community,” Anderson added. “I will do anything for you.”

Pat Kinney is a freelance writer and former longtime news staffer with the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier and, prior to that, several years at the Ames Tribune. He is currently an oral historian with the Grout Museum District in Waterloo. His “View from the Cedar Valley” column is part of “Iowa Writers Collaborative,” a collection of news and opinion writers from around the state who previously and currently work with a host of Iowa newspapers, news organizations and other publications. They are listed below. Clink on the links to check them out, subscribe for free - and, if you believe in the value of quality journalism, support this column and/or any of theirs with a paid subscription .

The Iowa Writers’ Collaborative