'Long, long time ago:' Waterloo journalists, civil rights and Buddy Holly in the '50s

Waterloo/Mason City reporter Jim Collison crusaded against segregation, covered Holly plane crash; Dick Cole took iconic Holly photo in Waterloo

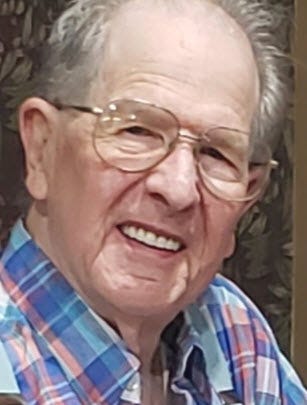

The confluence of Black History Month and “the day the music died” isn’t lost on Jim Collison. And not just because they both fall in February.

He covered that history as it happened – both Waterloo’s civil rights movement and the Feb. 3, 1959 plane crash that killed music star Buddy Holly - as a reporter for the Waterloo Courier, and the Mason City Globe-Gazette, respectively.

Meanwhile, in 1958 teenage Courier photographer Dick Cole shot what would become an iconic photo of Holly, that has been seen worldwide over the past six decades.

Both men, each in their own way, became part of history.

In the middle to late 1950s, Collison, who’ll turn 90 this year, was the Courier’s business beat reporter for the east side of Waterloo – where most of the city’s Black population lived in de facto segregation.

“I get to Waterloo and my wife and I, we’re just shocked. It was like suddenly we’re In the South,” Collison said. A white police officer, noticing Collison sitting in his car near the Courier reading the classified ads looking for housing, told Collison not to get a place on the east side of town. The implication was clear. “That was my first experience with segregation,” he said.

Collison had lived and worked with Black Bahamian workers at a Green Giant food canning plant at his hometown of Blue Earth, Minn. And he had Black friends in college at St. John’s University in St. Cloud, Minn.

“My father was totally blind from a very early age. And Dad would say, ‘I am not prejudiced because everybody looks the same to me.” It left a lasting impression on Collison, one of 13 children that included foster and adopted Latinx and Asian siblings. “I grew up with an open attitude,” he said. “My mother was extremely welcome to everybody.”

Part of his Courier duties were to cover local agencies and organizations, including the local chapter of the NAACP. That’s where he became friends with Black community leaders like Anna Mae Weems. And he and his family lived on the east side of town. He and his wife Val were social friends with Anna Mae Weems and her husband Eugene.

Collision pushed back against the segregation he found in Waterloo. He began writing a column for a local Black paper, the Star, under an assumed name, under risk of termination by the Courier. The column was called “Smitty’s Punches” and he wrote it under the byline of “Wellington Smith” – the surnames of two Black friends from Minnesota. He said that paper was started by the Rev. George T. Stinson of Payne AME Church.

When the Star folded, Collison started his own newspaper of Black and other community news, The Waterloo Progress, after leaving the Courier and while teaching for a year at St. Mary’s High School in town.

Collison wrote in the Progress that its main objective “is to print news and facts of interest to ALL Waterloo people, not ignoring news of interest to the city’s laboring people and not ignoring news of interest to the city’s minority people.”

While the paper printed news of general interest to all citizens, Collison said, “from the content, it was quite obvious that the target market for subscriptions” was the local Black population.

The Progress was quickly snuffed out by its much larger competition. Collison’s neighbor and advertising representative, J. Russell Lowe, a Black World War II veteran and a longtime Waterloo educator and community leader, discovered the Courier had dissuaded businesses from advertising with the Progress.

Without that interference, “I really believed I could make money at it,” Collison said, given the city's large Black population. The Progress lasted five issues, published in May and June. 1958.

Collison took a better-paying job at the Mason City Globe-Gazette in October 1958. Four months later, he covered the best-known story of his career – the plane crash that killed rock ‘n’ roll stars Holly, Ritchie Valens and J.P “The Big Bopper” Richardson following a concert at Clear Lake’s Surf Ballroom. His coverage was carried worldwide.

While that story brings Collison notoriety even today, and especially this week, he says it’s just a very tragic breaking news story --- unless taken in the context of the times then, and in the years that followed.

Collision says singer-songwriter Don McLean’s now-classic song “American Pie,” dedicated to Holly, accurately captured what many young adults like him felt in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s – as the optimism of the civil rights movement and hope for real change for good “landed foul on the grass,” in the words of McLean’s song. Events spiraled downward amid social unrest, racial strife and the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. The deaths of Holly, Valens and Richardson was a symbol of the lost innocence of the decade that followed – and the turmoil that continues today.

“A lot of people think the song is about the crash, The song isn't about the crash; The crash is a metaphor,” Collison said. “It’s a metaphor for the politics and the culture in America from the time of the crash to today. It’s a metaphor for what’s happened since the loss of innocence in the 1950s. The loss of innocence began in the 1960s and has continued through to where we are today."

Collison noted that, after leaving newspapers, he worked on John Culver’s first congressional campaign -- the longtime U.S. congressman and senator from Iowa who was a contemporary of the Kennedys. But due to the decade's tragedies, “I became very disillusioned,” he said, “and my disillusionment with politics has only gotten worse since then.”

He recalled “the enthusiasm I had in the late 1950s when I got involved with Blacks in Waterloo. And then Martin Luther King comes along, and the civil rights movement looks like it’s making progress on race relations. And what happened? We get what we have today.”

Collison, a widowed father of six adult children, with 11 grandchildren and many great-grandchildren, pushed away from social and political involvement a long time ago.

“I’ve gotten really big into meditation,” he said, having authored books on the subject. He has his own webpage and has taught at North Iowa Area Community College in Mason City.

While race relations in Waterloo and elsewhere have outwardly improved since the 1950s, subtle racism exists - something he said his adult Black granddaughter, now in her late 20s, experienced while attending the University of Northern Iowa in Cedar Falls.

”I don’t think it’s as bad as it was 50 years ago, but it’s still there,” Collison said.

He also expressed disappointment that a permanent memorial hasn't yet been erected in Waterloo commemorating Martin Luther King's November 1959 visit, an event made possible by his friend Anna Mae Weems..

“I could be real disillusioned if you talked to me long enough, but most of the time, I’m personally pretty mellow," said Collison, a lay minister with the United Church of Christ for more than 40 years. “The answer is to love. Love is the answer for everything.“

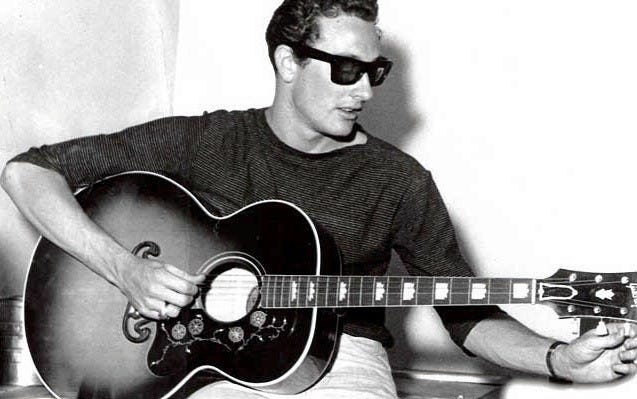

Cole’s Holly photo

Dick Cole was a 17-year-old part-time Courier photographer when he shot an iconic photo of Buddy Holly sitting on an icebox and tuning his guitar backstage before an April 28, 1958 performance at the Hippodrome on Waterloo's National Cattle Congress grounds. Holly was one of 17 acts performing as part of promoter Alan Freed’s “Big Beat Show.” Admission was $1.50.

Holly returned to Waterloo the following July for another performance at the Electric Park Ballroom, also on the Cattle Congress grounds, and autographed prints of Cole's photo of him.

The photo has appeared everywhere from Texas Tech University in Holly's hometown of Lubbock to Hollywood. Cole said Maria Elena Holly, the singer's widow, has said it is her favorite photo of her late husband.

Cole recalled he and his Waterloo West High School buddy and photo equipment caddy Dick Kline found Holly to be personable and "a regular guy" in conversation, even though elders in town still frowned upon the new music as socially taboo. Cole and Kline helped Holly and his band, the Crickets, unload their equipment for the Electric Park Ballroom performance, ingratiating themselves with the entertainers.

But when Cole asked the rock 'n' roll star to take off his sunglasses, simply for a better shot of his face, Holly said, “ ‘I never have pictures made without my glasses,’ " Cole recalled.

Holly, just in his early 20s, had a good time in Waterloo, Cole said, including water skiing on the Cedar River. He said Holly had planned to return to Waterloo in the summer of 1959, but fate intervened.

Cole, now 82, worked several years at the Courier in the late' 50s and '60s, He also had a stint at the Lincoln Journal-Star newspaper in Nebraska and worked for a time as a photographer for John Deere. In 1968, he started his own Waterloo photography business, which he operated for 40 years.

Cole said a lot of people in town still don't know about the Holly photo. But elsewhere, "for three days in February" every year, around the anniversary of the plane crash, "I'm famous." That’s when commemorative concerts are held such as the annual Winter Dance Party show at the Surf in Clear Lake.

While he's never made much money off the Holly photo, Cole said the important thing is to keep alive the memory of Holly and his influence on music and culture.

Iowa Writers’ Collaborative Columnists

Laura Belin: Iowa Politics with Laura Belin, Windsor Heights

Doug Burns: The Iowa Mercury, Carroll

Dave Busiek: Dave Busiek on Media, Des Moines

Art Cullen: Art Cullen’s Notebook, Storm Lake

Suzanna de Baca Dispatches from the Heartland, Huxley

Debra Engle: A Whole New World, Madison County

Julie Gammack: Julie Gammack’s Iowa Potluck, Des Moines and Okoboji

Joe Geha: Fern and Joe, Ames

Jody Gifford: Benign Inspiration, West Des Moines

Nik Heftman, The Seven Times, Iowa and California

Beth Hoffman: In the Dirt, Lovilla

Dana James: New Black Iowa, Des Moines

Pat Kinney: View from Cedar Valley, Waterloo

Fern Kupfer: Fern and Joe, Ames

Robert Leonard: Deep Midwest: Politics and Culture, Bussey

Tar Macias: Hola Iowa, Iowa

Kurt Meyer, Showing Up, St. Ansgar

Kyle Munson, Kyle Munson’s Main Street, Des Moines

Jane Nguyen, The Asian Iowan, West Des Moines

John Naughton: My Life, in Color, Des Moines

Chuck Offenburger: Iowa Boy Chuck Offenburger, Jefferson and Des Moines

Barry Piatt: Piatt on Politics: Behind the Curtains, Washington, D.C.

Macey Spensley, The Midwest Creative, Davenport/Des Moines

Mary Swander: Mary Swander’s Buggy Land, Kalona

Mary Swander: Mary Swander’s Emerging Voices, Kalona

Cheryl Tevis: Unfinished Business, Boone County

Ed Tibbetts: Along the Mississippi, Davenport

Teresa Zilk: Talking Good, Des Moines

To receive a weekly roundup of all Iowa Writers’ Collaborative columnists, sign up here (free): ROUNDUP COLUMN

We are proud to have an alliance with Iowa Capital Dispatch.