Iowans fought, died in first integrated Army units in Korea

Many still missing on anniversaries of Korea armistice, Truman desegregation order

Many Iowa soldiers served in combat at the confluence of some historic events this month.

Some laid down their lives for their comrades in the process.

Many are still missing.

This month marks the 70th anniversary of the signing of the armistice ending the fighting in the Korean War. It is also the 75th anniversary of President Harry Truman signing Executive Order 9981, desegregating the U.S. military.

Iowa soldiers were part of that history – including Black soldiers who were the first to serve, fight and die in integrated combat units. Many troops, regardless of color, are still in Korea where they fell.

President Truman’s executive order was signed July 26, 1948. The Korean armistice was signed July 27, 1953

The fighting ended, but many didn’t come home. Not even their remains. Some are only now being returned, like those of Pfc. Delbert White of Ottumwa.

Others, like George Earnshaw Bolden of Des Moines, have not.

More than 7,600 Americans are still unaccounted for from the 1950-53 war. More than 2,000 of them died in captivity as prisoners of war due to untreated wounds, malnutrition, torture or execution on death marches to prison camps.

A total of 8,000 Iowans served, more than 500 were killed and 70 are still missing in action; more than 30 of them died as prisoners of war.

White was among the POWs. Bolden may have been.

White was a corporal in D Company, 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion of the U.S. Army’s 2nd Infantry Division in late 1950. Following a successful amphibious landing at Inchon, U.S. and other United Nations troops advanced into North Korea, only to be overrun by hundreds of thousands of Chinese Communist troops entering the war across the Yalu River from China into North Korea.

White and many other 2nd Infantry Division soldiers were captured by the Chinese People’s Volunteer Forces, as the Americans attempted to block the enemy and allow the rest of the division and a large portion of the U.S. Eighth Army to escape south. They held off the enemy forces as they attempted to withdraw through a gauntlet of enemy fire near the North Korean village of Kunu-ri until, finally, they were overrun. White was captured Dec. 1, 1950.

The Chinese identified White as a POW in 1953 but according to returning prisoner accounts he was last seen alive March 18, 1951. He reportedly died of malnutrition in captivity. He was 20.

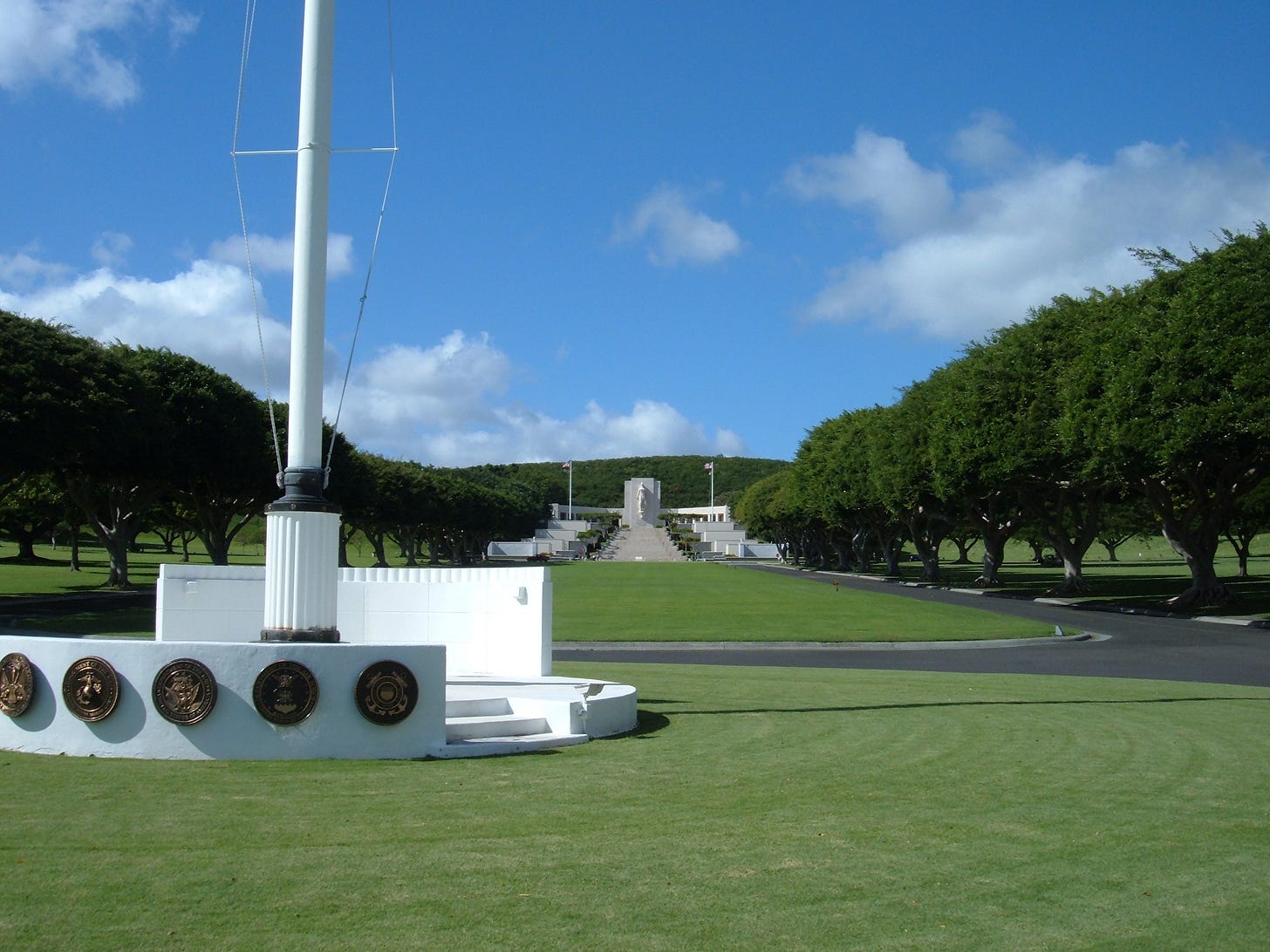

Following the armistice, as part of an “Operation Glory” exchange of remains between the combatants in 1954, the U.S. received more than 500 sets of remains of soldiers and Marines. They were interred at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at the Punchbowl crater near Honolulu, Hawaii.

With the advent of modern DNA technology, remains of prisoners from White’s POW camp were disinterred by the U.S. Department of Defense POW-MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) for identification in 2019 at Joint Base Hickam at Pearl Harbor. White’s remains were identified last Sept. 27. His remains were laid to rest June 16 next to his parents at Calvary Cemetery in Ottumwa. He was one of a family of eight children. He was survived by a brother and a sister, toddlers when he died.

Less than 10 miles from Kunu-ri where White was captured, just two days earlier, George Earnshaw Bolden was fighting for his life and those of his comrades.

Bolden and a company of 100-150 of his brothers in arms were thrown into battle in a similar blocking action. Only about a third of them would survive.

Bolden served in E Company, 2nd Battalion, 35th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Army’s 25th "Tropic Lightning" Infantry Division at Yongbyon in North Korea, near Ipsok along the Kuryong River, a northern tributary of the Chongchon River.

According to unit histories, with the main line of the 35th Regiment collapsing, Bolden’s E Company, previously resting in the rear, was thrown into the front line. They held off the advancing Chinese, but E Company was reduced to a platoon of a few dozen men by the end of the battle. And, surrounded and roadblocked to the rear, the remnants of the 35th had to fight their way out. By the time they re-connected with the 25th Infantry Division on Nov. 28. Pfc. Bolden was reported missing in action.

In December 1953, after the armistice in July of that year, he was declared dead. However, his mother told the Des Moines Register she was “positive” her son appeared in a photo released by the Chinese of about 50 American prisoners that appeared in the Jan. 31, 1951 Register. Despite that, his name never appeared on any POW lists.

Bolden, like White, was one of eight children. He’d entered the Army in 1949 at age 18. His mother told The Register in a January 8, 1954 article she’d last heard from him in a Nov. 19, 1950 letter in which he wrote, “They’ve started shooting again --- I’ll finish this when I get a chance.”

His remains have never been returned or identified. His name, like White’s, was listed at the Courts of the Missing at the Cemetery of the Pacific at the Punchbowl in Hawaii.

A few months after George Bolden was declared missing, his parents received a letter from his brother, Martell W. Bolden, that Martell had been wounded by a hand grenade in April 1951, serving with the Army’s 24th Division, which had also been decimated in the Chinese offensive. Martell survived the war.

It was just as U.S. forces under Gen. Matthew Ridgeway, following President Truman's relief of Gen. Douglas MacArthur from command, were able to finally blunt the over-extended Chinese troops' advance, after which the fighting settled into a bloody stalemate along the 38th parallel until the armistice.

But before that armistice, another trailblazing Black soldier from Iowa gave his life.

U.S. Army Pfc. Claude R. Smith of Des Moines was among the first African-American soldiers in the 179th (Tomahawks) Infantry Regiment of the 45th Infantry Division. In 1950 it was a racially segregated, all-white Oklahoma National Guard unit. By 1952 it was fully integrated with many regular-Army enlistees and draftees, including Pfc. Smith.

The unit, the first National Guard unit deployed to the Far East since World War II, was sent to Korea to relieve the 1st Cavalry, which had sustained heavy casualties. The 45th defended roads around Chorwon into the South Korean capital of Seoul and fought Chinese troops all along the battle line near the 38th parallel in 1952, intercepting enemy patrols, raiding outposts and withstanding Chinese attacks.

The unit was engaged in a battle on Old Baldy Hill at about the time Smith’s was killed in action,on Nov. 20, 1952. He was 21. His body was returned in January 1953 and he was buried at Glendale Cemetery in Des Moines. He had worked as a busboy at the Hotel Savery downtown before entering service. He was survived by his mother and six siblings.

The Grout Museum District's Sullivan Brothers Iowa Veterans Museum in Waterloo is gathering biographies and photos of all Iowans killed in the Korean War for its "Faces of the Fallen" exhibit in the permanent Korean War section of the museum. Contact the museum at the link here or at (319) 234-6357 to submit or obtain more information.

The Defense POW-MIA Accounting Agency continues its work identifying the remains of missing Amercan military personnel of all eras and conflicts. More information is avaiable at dpaa.mil and the agency’s Facebook page.

The Iowa Writers’ Collaborative

Thank you for telling the stories of these brave young men. Each one of them, gone too soon.