MARSHALLTOWN —- Ralph Alshouse hadn’t even seen an airplane until he was in his teens.

That was about 90 years ago. He’d see a lot of planes — from the inside —throughout World War II.

Now 101, he can recall a few times he may not have lived to 21 by the time the war ended in 1945.

But he knew from his dad, who saw trench warfare in World War I, that if he went to war, an airplane was where he wanted to be.

Alshouse, a resident of the Iowa Veterans Home in Marshalltown, was a Navy pilot who delivered or “ferried” planes all over the country from the manufacturer to be loaded on to aircraft carriers, or brought battle-worn craft into repair shops. He was part of Ferry Squadron VRF-2, based in Columbus, Ohio, but flew to installations nationwide.

Growing up near Oelwein and graduating from high school in Stanley in 1941, he went into the Navy shortly after Pearl Harbor.

The duty was hazardous enough, flying various aircraft which had equally varying and challenging capabilities. He had 13 emergency landings during the war, out of 146 flights and more than 1600 hours’ flight time, involving 28 different kinds of naval aircraft, ranging from small Piper Cub medical evacuation ambulance planes, to Marine Corsair and Navy Helldiver fighter-bombers to multi-engine heavy bombers like the B-24 Liberator or its Navy version, the PB4Y-2 Privateer.

On one nighttime training flight, he dodged an encounter with a tropical storm over the Gulf of Mexico. Two other cadets weren’t as fortunate.

“We were flying out of Pensacola Naval Air Base (in Florida), flying (Vought) OS2Us (Kingfisher observation float planes). Each of us had one. It was the final phase of our training before we got our wings. And three of us went out, and I was the only one to make it back. We were in the Gulf. We hit a line cloud out there they didn’t know about. And I told the other two guys, ‘I’m gonna turn (away from the storm); so let’s all turn.’ They said, “No, no our orders are to go straight.’ "

He radioed out and received clearance to turn; the other cadets didn’t pick up the message over the static. He radioed back to them after making the turn but received no answer.

“I thought ‘Well, I better head back to base.’ There was no light, darker than hell, and my first thought was, ‘Oh s--t, I must be lost’ And then all at once I saw the flicker of the (airfield) beacons. When you’re think you’re lost out at sea, in the middle of the night, and you see a beacon, boy, that makes you feel better.

“We went out the next morning with everything that flew; I think there was eight to us,” looking for the missing pilots, Alshouse said. “And we didn’t find a thing.”

On another occasion, he was pulling a target behind him for gunnery practice for other planes — only to get shot at himself. He discovered dents in his own craft after landing. Had the pilots been using a higher caliber ammunition in practice, the outcome might had been far different.

While ferrying a small medical evacuation plane from Florida to a shop near Memphis, Tenn. for repairs — basically a flying ambulance with space for one patient in the rear of the cockpit — he touched down at the scene of a serious multiple-injury automobile accident and picked up the victim in the worst condition for transport for medical treatment. He taxied off the pavement as highway patrol officers at the scene cleared the road for him to take off.

Among other narrow escapes, he also made a forced landing in Pittsburgh of a Corsair fighter plane on fire. In another instance, he and comrades rescued another pilot from a downed, burning plane before it exploded.

Alshouse, a 1948 graduate of Iowa State University in dairy science, is retired from work as a farmer and Farmers Home Administration farm appraiser at different locations around the state. He also served a stint as the mayor of Seymour in Wayne County near Centerville southeast of Des Moines.

He’s a former chairman of the Rathbun Area Solid Waste Commission. In 2018 was recognized by a recycling customer, Indian Hills Community College in Ottumwa, for helping provide commission land to the college to start a sustainable agriculture program.

He found another more recent calling — as an author. He jotted down memories of his service to his offspring. A fellow former military pilot he met at a veteran dinner in Seymour, retired U.S. Marine Corps Capt. Mark Hewitt, suggested he write a book. He had no intention of such thing, but discovered he in fact already had enough material for one, if he combined all his written recollections.

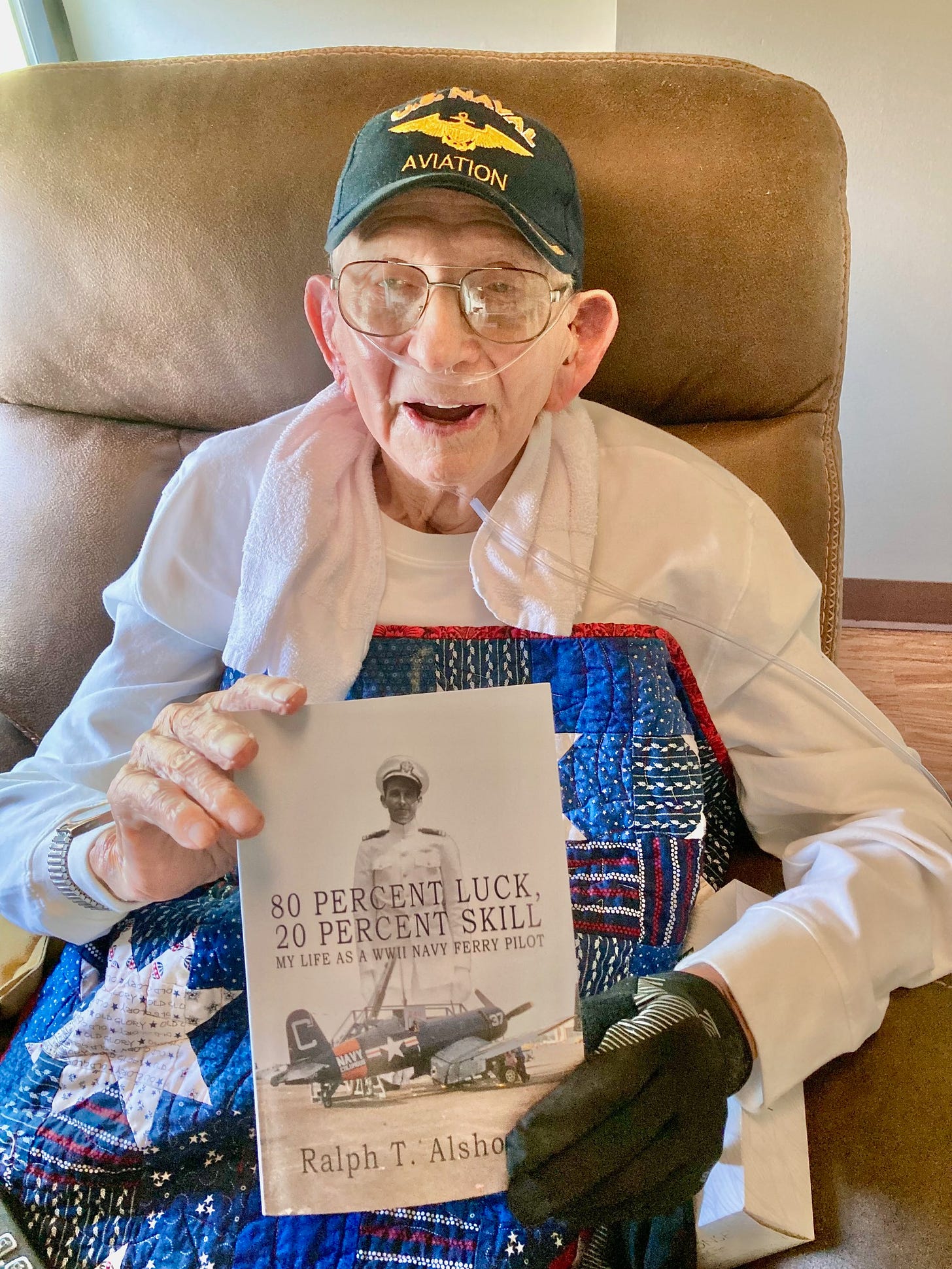

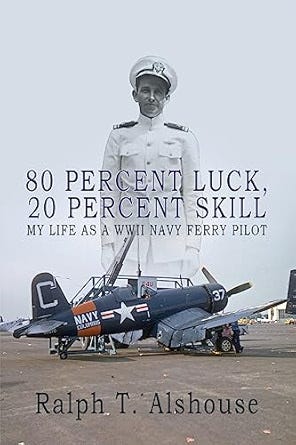

He fused all those reminiscences into a book, entitled “80 Percent Luck, 20 Percent Skill.” It was published in 2023 and is available online on Amazon and through Barnes & Noble.

Alshouse saw his first plane as he was working for his dad in the farm field near Oelwein.

“I was cultivating beans one day. It landed in the hay field south of where I was cultivating beans,” he said. “Two gentlemen in business suits got out,” a car picked them up, “and they left the airplane.” They may have been going to a nearby farm on business on a property that had been through foreclosure.

His father came over from an adjacent field. Ralph came up on the plane, a Club Cadet, and peeked inside. “My God, all those instruments and all those controls.” he said. “I told Dad it must take a genius to fly one of those.

“That gave me the urge,” he said, “after Dad told me about all the guys that was killed in no man’s land in World War I. There was so much gunfire the trees fell over and they stacked the bodies up like cordwood and get behind them (for cover) to shoot. That helped me commit to being in the air instead of on the ground.”

He saw advertisements in the local paper seeking applicants for flight training. Lacking applicants, the standards were lowered from a four-year college degree, to a two-year degree, to high schools. “That’s when I stepped in,” he said. He and other enlistees didn’t know the different between the advantages of different branches of service, “we just wanted to fly.”

He took testing and training in Decorah, Minneapolis and pre-flight training at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, where he became a champion boxer in his class. “I never had a pair of boxing gloves on before, but I won the championship,” though he quipped, “My nose always got in the way.” He was bloodied a few times.

“We had about a 25 percent washout rate at Iowa City,” he said. He received flight training at the naval air installation at Wold Chamberlain Airport in Minneapolis, and then to Pensacola for training in catapult-launched scout planes like the kind used on various naval ships at that time.

“I got shot off a catapult three times in flight training,” he said “If you think you know what happiness is, that’s when you’re happy, that you’re still alive” and flying after a catapult launch.

Ralph still flew some in civilian life after the war. He had an ultralight craft and still has a trophy from a glider competition he won in 1970.

And his flying skills allowed him to avoid another close call — as a farm appraiser.

When a shotgun-wielding farmer ordered Alshouse off the property, he complied —- but still flew over the farm and conducted the appraisal by air.

He discovered that on many occasions in peacetime as well as war, it’s still safer by air than on the ground.

Pat Kinney is a freelance writer and former longtime news staffer with the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier and, prior to that, several years at the Ames Tribune. He is currently an oral historian with the Grout Museum District in Waterloo. His “View from the Cedar Valley” column is part of “Iowa Writers Collaborative,” a collection of news and opinion writers from around the state who previously and currently work with a host of Iowa newspapers, news organizations and other publications. They are listed here. Clink on their individual links to check them out, subscribe for free - and, if you believe in the value of quality journalism, support this column and/or any of theirs with a paid subscription. Thank you.

Not thinking you'd live to be 23 and talking about it 80 years later is a bit mind-boggling.

What an amazing man! Thx for sharing his story.