From Deere worker to region chief, Waterloo labor leader looks back

Ron McInroy retires as UAW regional head; stared with Deere in Waterloo in 1979

It probably was nearly a sure thing Ron McInroy was going to be a union man.

Good jobs were anything but sure anywhere he or his family worked. He knew he'd have to fight fot them.

What he may not have anticipated, however, was that he would be fighting for tens of thousands of workers and their families all across the central and northwestern United States.

McInroy, a native of Charles City who began working at John Deere’s Waterloo operations in 1979, recently retired as regional director of the United Auto Workers in the central and northwestern United States.

He held that position for 12 years, after working his way up from the shop floor at Deere in Waterloo, where he was elected a union steward after two years on the job.

In that time he’s seen massive layoffs during the 1980s farm crisis, lockouts, strikes and plant closings.

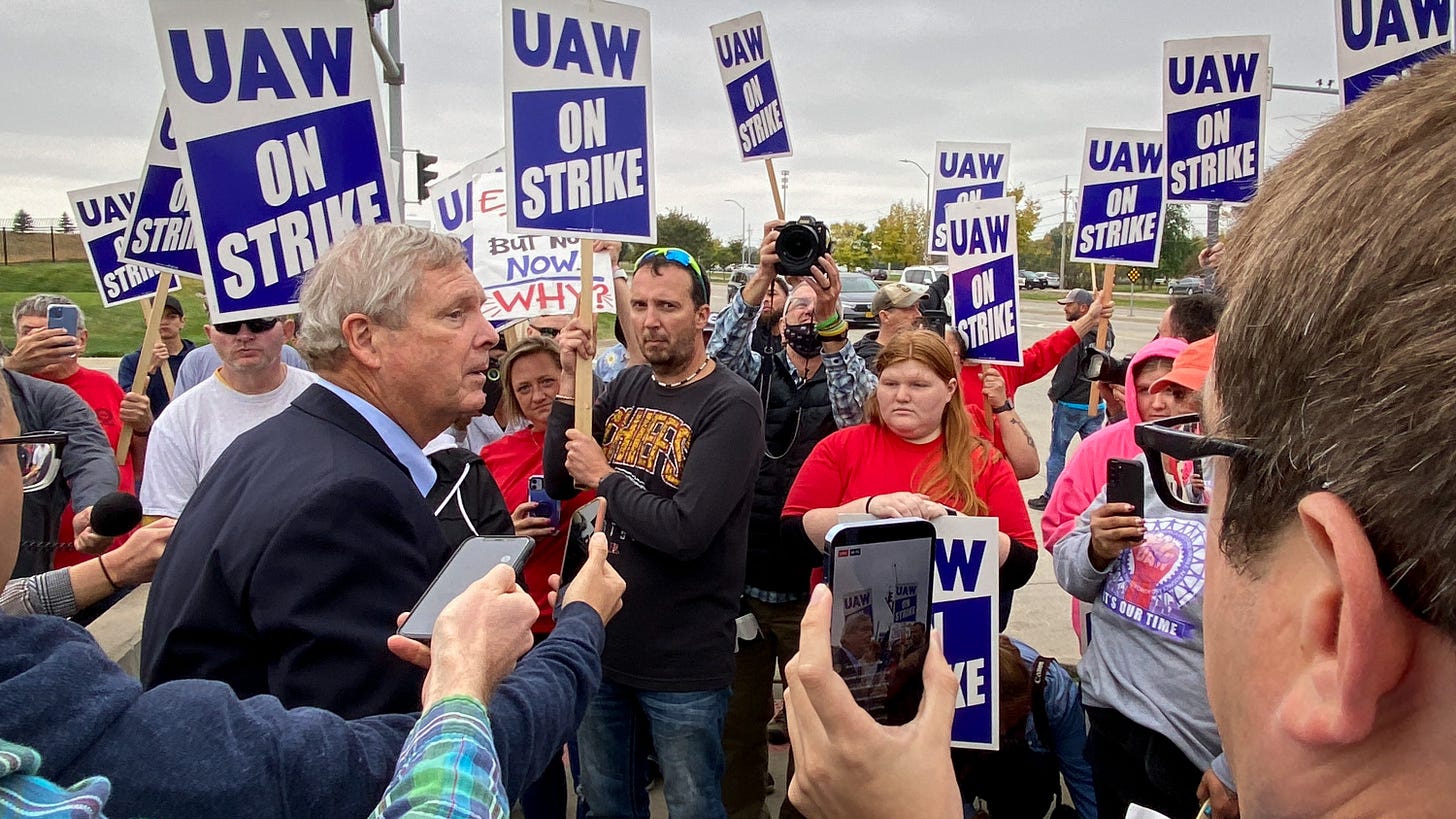

The strikes included a five-week work stoppage at Deere in 2021, the first in 35 years, in which two tentative agreements were rejected before a contract was reached.

But he also saw a major billion-dollar redevelopment of Deere’s Waterloo operations over the past two decades and generational changes in the needs of the manufacturing workforce.

Through all that, he said, though taking on positions of increased responsibility and complexity, his 20 years working at Deere in Waterloo and walking the shop floor on behalf of the union kept him grounded and focused on what really mattered – the welfare of union-wage working members and their families.

Waterloo is home to Moline, Ill.-headquartered Deere’s largest North American manufacturing complex. Deere is Waterloo’s and Iowa’s largest manufacturing employer and United Auto Workers Local 838 is one of the largest private sector union locals in the state and the largest within Deere.

“I started right downtown as a yard factory laborer, the bottom of the barrel,” said McInroy, 65, a graduate of Charles City High School and one of 15 chldren. “The reason I know a little bit about the UAW is because my brother and my uncles worked at White Farm.” White Farm Equipment was a Charles City agricultural equipment manufacturer which sustained significant layoffs beginning in the mid-1970s. and eventually closed in 1993.

“I got a firsthand look at pensions being raided during that time,” he said.

He also worked at Salsbury Laboratories in Charles City, a nonunion shop which also saw significant job reductions when it ran into environmental waste disposal issues with the state. He was laid off in the late 1970s.

“So I signed up with John Deere. I got called back after six months up there (at Salsbury). But then John Deere called and I came down, and the guy said, “Do you want to start today?’ Jan 3, 1979 is when I started.” He got a tooling position in three or four months, still at the downtown facilities, where tractor components such as transmissions are manufactured.

That was when Deere employed a record 16,000 workers in Waterloo. The popular notion was that one could be virtually “hired off the street’ to work at Deere, or the other major employer in town, The Rath Packing Co.

Then the 1980s recession and farm crisis hit.

“I got hit in the first layoff. It was ’80. I was laid off six, eight months,” he said. He was called back from layoff to the Deere Tractor Works on East Donald Street in northeast Waterloo, where are the company’s large row-crop tractors are assembled. He worked there before being recalled back to his old position downtown, working second shift, as he would for 20 years.

“Really, the reason I got to stay? I got elected (union) steward in 1981,” McInroy said. He came back from layoff and some of his colleagues asked him to run for steward.

“I said ‘What’s that?’ “ he laughed. He acquainted himself with the responsibilities associated with the post and decided to run.

Because of workforce reductions, the number of stewards had to be reduced proportionately, similar to legislative reapportionment. McInroy was thrown into a muti-way race, with multiple rounds of runoffs. Her survivd two runoffs, but was up a seasoned incumbent opponent in the final vote, and faced certain defeat.

Then his opponent surprised him.

“He came to me and he said he liked what I was doing and that they need somebody young, “McInroy said. “He took me around and introduced me to all the mechanics,” as well as other trades in the steward area. “So that’s how I got elected. He basically helped me get elected.”

McInroy held that post through continued layoffs and a bitter five-month strike and lockout in I986-87, the longest collective bargaining-related work stoppage in the company history of talks with the UAW. Through continued layoffs, Deere’s Waterloo employment dropped to around 5,000; it’s at about 5,500 today, more than half of which are union-wage UAW-affiliated workers.

In 1993, McInroy was elected to a committeeman position, representing workers in the Deere Waterloo Foundry, as well as skilled trades employees in the Waterloo Works and second shift in the Product Engineering Center in Cedar Falls. At that time, company and union negotiated a two-tier wage structure with a lower starting wage and benefit in exchange for a promise by Deere to bring outsourced manufacturing work back into its factories and preserve jobs. Deere said at that time the agreement allowed the company to “repopulate’ its plants .

The goal, McInroy said, was “how do you get these jobs back in Waterloo and every where in the (Deere) chain?” A master collective bargaining agreement governs pay, benefit and working conditions for Deere works in UAW locals throughout the company – the largest of which is in Waterloo.

“When you go from the local to bargaining, you realize you’re not just bargaining for Waterloo at that point; you’re bargaining for the whole chain” – twice as many workers plus their families.

“Each step you go up, it’s a bigger picture, a broader (worker) base,” McInroy said. “You have more involvement and then you understand what goes into the business — the union and that of the companies (whose works) you represent.”

In 2001, Deere also launched a massive multi-phase modernization or “redevelopment” of its Waterloo operations, in coordination with the union-wage work force. It involved demolishing some of its outdated older multi-level manufacturing building and constructing new single level ones, modernizing the Waterloo Foundry with a new melt process and re-equipping and streamlining assembly lines.

After being part of the bargaining committee which negotiated the 2003 Deere-UAW master agreement, McInroy was put on full-time UAW staff in 2005, serving workers at companies of varying sized in addition to Deere.

“The best part about that is you get to use the skill sets you learned early on from your local leadership here and you get to use it with all the different sizes and different types of companies you have,” he said. “I had like 15 contracts then and they were all different sizes of companies, types of companies. But you get to use the things you learned here (in Waterloo) and apply them. That’s always the advantage of being union; you can talk to each other and bring different concepts to your workplace and share the ideas to make it better.”

In that regard, coming from a already large UAW local was an advantage, McInroy said. “The other things I was always very fortunate of on Waterloo was, I had leadership to work with to mentor me.”

But as a UAW staff representative, working with different employers and workforces. “you got to work directly with the owner and the employees. Solutions were easier to come up with. In a larger corporation there’s layers and layers that you have to go through, both sides.” And with smaller workplaces and workforces “they both understand the repercussions quicker. Everything’s faster, the timeline’s faster.”

McInroy was a UAW servicing representative from 2005-08, “I was still in Iowa,” he said. “We drove about 55,000 miles a year. I had locals in Des Moines, I had locals in Cedar Rapids and I had locals here.

“And I had Maytag in Newton, so I went through that too,” McInroy said, when the washing machine manufacturer wound down its operations.

“I’d seen what’d happened in Charles City,” with White Farm Equipment, he said. “Now I get see it a second time when Maytag closes,” in 2005-06. “You see four or five generations of families seeing jobs leave the community. It changes the community. You realize that. It’s like having a cloud coming over your town.”

In 2008 he became assistant regional director, and relocated to Illinois a year later. He then served three four-year terms as regional president.

When McInroy was elected regional director in 2010, “we had nine states with 40,000 active members and 120,000 retirees,” McInroy said. Due to a merger, the region has grown to 17 states with 60,000 members and double the previous number of retirees. “To get familiar with all our different manufacturers, there's a lot of travel. You have 25- to 30 staff you're over. The thing I tell people is, as you go higher in the institution, you have the ability to work with different layers, not only companies and the union, but also government.

“Everything ties together, how your laws, all your court rulings,” he said. “It's working with governors, working with mayors” and companies themselves to help workplaces and communities. For example, federal auto emissions standards directly affect ethanol, which affect corn production, which affects farmers and their demand for agricultural. equipment like Deere makes. That takes labor-management cooperation.

”A lot of time we will work with companies on laws that benefit our members. We have to,” McInroy said. “Our jobs, the jobs with the factories, continue to pay the wages for our members, which helps our communities.

"When you become a (regional) assistant director or director, you're no longer taking care of just your local," McInroy said. "Yes, you belong to your local, but your focus is every member in your region, how do you make their lives better, in the same way you did locally."

There were challenges and more plant closings during his time as regional director. And the most recent Deere-UAW labor agreement was approved on a third vote — not by a majority of members of Local 838 in Waterloo, by enough workers in all the other locals that it was adopted chain-wide. But McInroy maintains the agreement is one of the best in the industry, if not the best, which workers are now seeing the benefits from. It includes a restoration of cost-of-living adjustments ( or “COLA”) in wages — important in inflationary times — and other benefits down the road in workers’ careers.

"It's a ride," he said of his position. "It's really an opportunity to help people --- a lot of times when they don't even know it." Workers are justifiably absorbed in their jobs and their families' lives, and may not understand the full ramifications of a labor agreement until they need to utilized its provisions later in their working careers or lives.

"If you're doing it right, the enjoyment you get is the success you see for the members and the communities. We do a lot in the communities too,” McInroy said. “You’re only there for a short period of time and you do the best you can do to make it better than when you got there.”

McInroy's region also has its own education and training center for future leaders - The Pat Greathouse Education Center in Ottawa, Ill. New, more efficient regional offices are now co-located there.

"That's our pride and joy," he said, because it’s an investwent in the union’s current and future leadership."We have the ability to meet with our members from our locals all year round. "You get to teach your locals everything they need to know to be a good union leader. What you're doing is providing them the tools to be good local leaders."

But, McInroy said after three terms and 12 years as regional president,"that's enough," he said. "It's time to go spend time with your family.”

The key to being a good union official is to not lose focus on the members, McInroy said. "You're serving membership, " he said. "Whether I was a steward, a international rep, assistant director, (regional) director, you're still serving the membership. Just in different capacities. If you don't forget where you came from, it makes it easy."

Iowa Writers’ Collaborative Columnists

Laura Belin: Iowa Politics with Laura Belin, Windsor Heights

Doug Burns: The Iowa Mercury, Carroll

Dave Busiek: Dave Busiek on Media, Des Moines

Art Cullen: Art Cullen’s Notebook, Storm Lake

Suzanna de Baca Dispatches from the Heartland, Huxley

Debra Engle: A Whole New World, Madison County

Julie Gammack: Julie Gammack’s Iowa Potluck, Des Moines and Okoboji

Joe Geha: Fern and Joe, Ames

Jody Gifford: Benign Inspiration, West Des Moines

Beth Hoffman: In the Dirt, Lovilla

Dana James: New Black Iowa, Des Moines

Pat Kinney: View from Cedar Valley, Waterloo

Fern Kupfer: Fern and Joe, Ames

Robert Leonard: Deep Midwest: Politics and Culture, Bussey

Tar Macias: Hola Iowa, Iowa

Kurt Meyer, Showing Up, St. Ansgar

Kyle Munson, Kyle Munson’s Main Street, Des Moines

Jane Nguyen, The Asian Iowan, West Des Moines

John Naughton: My Life, in Color, Des Moines

Chuck Offenburger: Iowa Boy Chuck Offenburger, Jefferson and Des Moines

Barry Piatt: Piatt on Politics: Behind the Curtain, Washington, D.C.

Mary Swander: Mary Swander’s Buggy Land, Kalona

Mary Swander: Mary Swander’s Emerging Voices, Kalona

Cheryl Tevis: Unfinished Business, Boone County

Ed Tibbetts: Along the Mississippi, Davenport

Teresa Zilk: Talking Good, Des Moines

To receive a weekly roundup of all Iowa Writers’ Collaborative columnists, sign up here (free): ROUNDUP COLUMN

We are proud to have an alliance with Iowa Capital Dispatch.

I have seen very few stories on the operation of the UAW in Iowa, so I really appreciated this one!