'Friendly Fire' 50 years later: Waterloo vet looks back

Standing up for fallen buddy Michael Mullen's family shaped Martin Culpepper's life, career

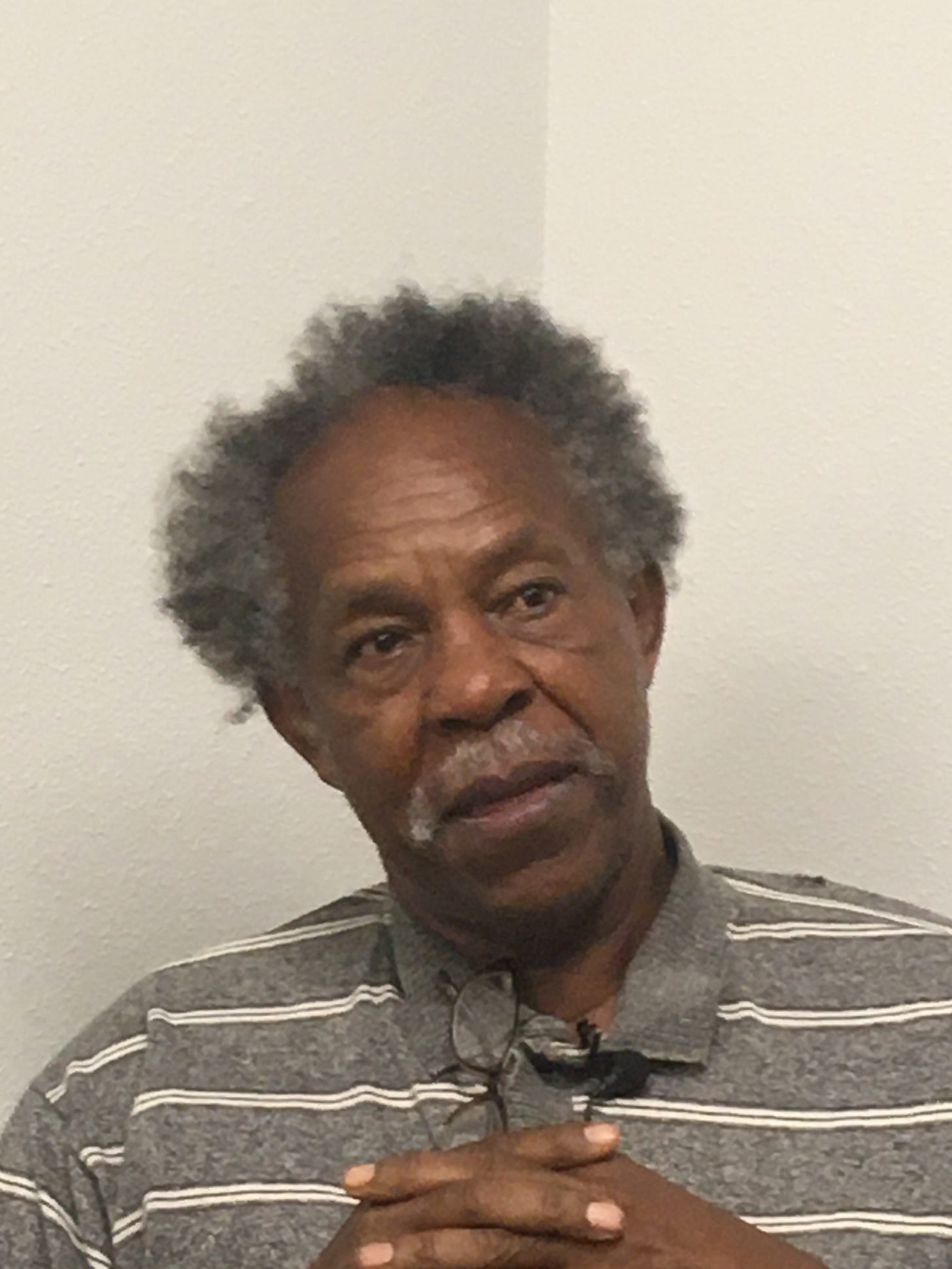

Martin Culpepper didn’t stand for injustice. Not for an Army buddy killed in Vietnam, nor for others of color in Culpepper’s chosen trade.

In fact, it was because he stood up for his fallen friend – Michael Mullen, killed by friendly fire – that Mullen’s folks, Gene and Peg Mullen of La Porte City, arranged for Culpepper to be trained as an electrician and eventually go into business on his own.

That was 50 years ago this year. It’s something Culpepper still becomes emotional over. It didn’t matter that Culpepper was Black and the Mullens were white. What mattered was what was right. He befriended them, they befriended him and he wasn't going to let them down.

“Gene and Peg are my second family,” said Culpepper. “I would never do anything within my ability to disappoint them, or me. They knew I was capable. I don’t like to disappoint people in anything I do. You do a job, you do it right."

Culpepper worked more than 40 years in his trade, more than half that time self employed, as Martin Culpepper Electric. He also was president of the Cedar Valley Minority Contractors Association and a frequently outspoken advocate for minority contractors, especially when it came to government contract work.

Culpepper wouldn’t have been in his life’s vocation had it not been for the Mullens.

He befriended them by telling them the truth about their son’s death. Michael was killed by a shrapnel wound from U.S. artillery Feb. 18, 1970. He and Culpepper served together in the U.S. Army’s 198th Light Infantry Brigade, 23rd Infantry (Americal) Division.

Culpepper was the first one to write the Mullens as to how their son died. He had helped dig the foxhole where Michael was killed in his sleep.

"We were friends because we were both from (around) Waterloo," Culpepper said. "We were talking about what were were gonna do, we were gonna get home and come out to the (Mullen) farm."

Their platoon had just dug foxholes to bed down for the night. In fact, Culpepper and Mullen had been ordered to change positions before a U.S. artillery round came up short and exploded above their position.

"He got my foxhole and I got moved. Very easily, that could have been me," Culpepper said. "The round was short, hit above him approximately 60 feet, and the blast went down. Mike took a little piece of shrapnel about as big as your thumbnail in the back. He must have been laying on his side ... it got his lungs and he was gone. "

Culpepper's letter to the Mullens indicated the Army was covering up the circumstances surrounding Michael's death. "They just told bunch of lies," Culpepper said. "I knew his address, so I wrote his folks and told them what happened. The Army had told them that we got overran by the enemy and that he had gotten killed in a firefight. Which was totally untrue. So I wrote. It is what it is. You don't lie. Very few excuses to lie about a man getting killed."

Culpepper told the truth about Michael’s death despite being offered military promotions.

"I told them to stick it where the sun don't shine," he said.

A superior officer "didn't like my reply.” he related. “I said, "Whaddya gonna do to me?' There wasn't a whole lot they could do to me. Besides that, I had the support of everybody else. The guys that I counted on, they were there. We know what happened. Whatever happened, happened. They shouldn't have lied about it, simple as that."

Peg Mullen took her outrage to her U.S. senators and she and Gene used the death benefit the family had received from Michael's death to pay for large antiwar advertisements in The Des Moines Register.

The so-called "Friendly Fire" incident attracted national attention, prompted a bestselling book by C.D.B Bryan and a 1979 Emmy Award winning television movie of the same name. Carol Burnett and Ned Beatty played Peg and Gene Mullen.

It also put Peg Mullen at odds with Michael's brigade commander — Col. H. Norman Schwartzkopf, later a general and a hero of the 1991 Persian Gulf War. Schwartzkopf said Michael Mullen's death was a accident -- that the artillery round he had ordered had struck a tree near their position enroute to a target -- but the Mullens never accepted that and blamed Schwartzkopf for their son's death.

"They got more than a few people's ears," Culpepper said of the Mullens.

When Culpepper got home from the service, in early 1971, he went to work for The Rath Packing Co. in Waterloo and, after a time, he said, "I went down and met Peg and Gene Mullen.”

They bonded, but it was tough love.

"He (Gene) was tougher on me than my dad was, being that he was a farmer," Culpepper said, but "they always treated me like one of the (surviving) kids. I mean really, seriously, one of the kids."

In 1973, the Mullens invited Michael for dinner one evening.

"We had a nice dinner, and then they say, they want to talk to me, " Culpepper said. They told him they had made a decision about his future. Culpepper was initially indignant at what he perceived as their presumptiveness, but the Mullens urged him to listen.

"The decided I wasn't going to work at Rath Packing Company anymore, because I could do better." They had made arrangements for him to be trained as an electrician through the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 288.

"It surprised me a lot," Culpepper said, wiping away tears. "They were everyday farmers but they were Christian people.”

When Culpepper found a house he wanted to buy in Waterloo, Gene wanted to see it. Gene was working a second job at John Deere in town and stopped out after his work shift to see the house. He met Culpepper there, checked out the place — and wrote Martin a check on the spot to get the house.

"If that ain't family, what do you call family?" Culpepper said, wiping his eyes. " I call them my adopted white family. People look at me; think I'm joking. I say, 'No, I had two families.’

“But he (Gene) was tough,” Culpepper said. “He expected certain things out of you. Period."

Gene passed away in 1986; Peg remained active in peace issues until her death in 2009 at age 92. She authored her own book, “Unfriendly Fire: a Mother’s Story.” She stood up for peace activist Cindy Sheehan, who lost a son in Iraq in 2004, when Sheehan picketed outside the White House and President George W. Bush’s Texas ranch. Peg received numerous honors from peace organizations and was inducted into the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame.

As president of the Cedar Valley Minority Contractors Association, Culpepper displayed a lot of Peg’s activism. He was undeterred from succeeding in his business and helping others succeed as well. When he felt government entities and white majority general contractors were only paying lip service to equal opportunity in government contracting work , he picketed, showed up at government meetings, even involved the U.S. Department of Justice.

In 1999, he picketed Gilchrist Hall, the administration building on the University of Northern Iowa campus in nearby Cedar Falls, for a few hours one afternoon to draw attention to what he said was university admininstrators' inattentiveness to policies regarding "targeted small businesses" like himself -- primarily minority and women contractors.

He has maintaned state and local goverments can do a better job of making sure disadvantaged business enterprises -- minority- and women-owned businesses — get and equitable share of government work, and that general contractors on goverment jobs use proven minority and women subcontractors.

If everyone pays taxes, Culpepper maintains, everyone, as taxpayers as well as entrepreneurs, should have a chance at a piece of the pie - especially government-contracted work in his own community.

He wanted to work for himself and didn’t let naysayers or bureaucratic obstacles stop him. “I never paid attention to people, because this is what I wanted to do,” he said. “Would I do it all again? Yeah. The opportunity is supposed to be there. There's enough money on the table for everybody to play.

"You had no problem sending me to war," he noted.

“I always had one ‘problem:’ I don’t like to see somebody being taken advantage of and being wronged when the person doing it knows it’s wrong,” Culpepper said.

That’s been true for him whether its a contractor trying to get work, or the bereaved family of a fallen brother in arms.

Pat Kinney is a freelance writer and former longtime news staffer with the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier and, prior to that, several years at the Ames Tribune. He is currently an oral historian with the Grout Museum District in Waterloo. His “View from the Cedar Valley” column is part of “Iowa Writers Collaborative,” a collection of news and opinion writers from around the state who previously and currently work with a host of Iowa newspapers, news organizations and other publications. They are listed below. Clink on the links to check them out, subscribe for free - and, if you believe in the value of quality journalism, support this column and/or any of theirs with a paid subscription .

The Iowa Writers’ Collaborative

Touching story!