Evansdale Marine survived costly ship rescue battle at end of Vietnam War

Mayaguez 50th anniversary events set in Georgia and Washington, D.C.

“In the fog of a hard battle gone wrong, they held high a lantern of courage and hope that illuminated the way home with honor.”

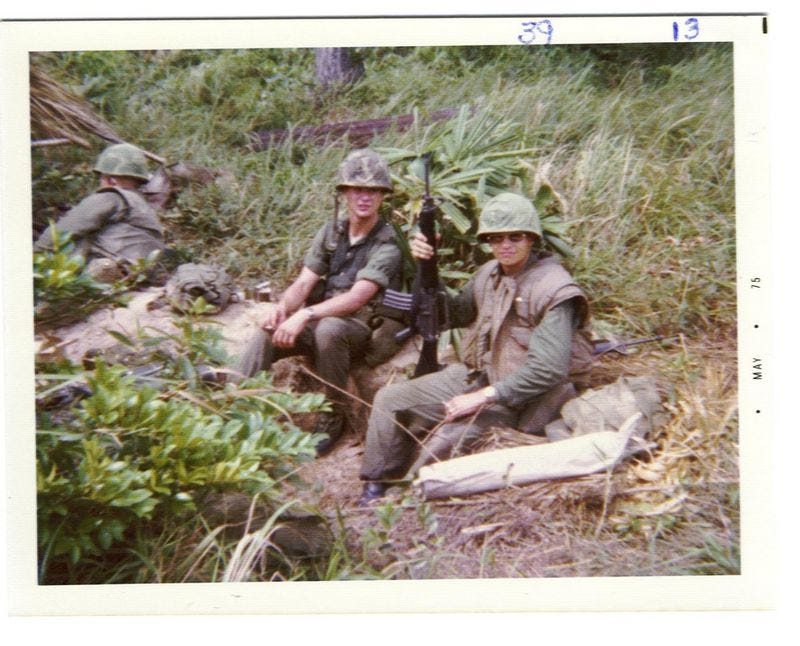

—U.S. Sen John McCain, dedication of Mayaguez Marine Corps Memorial, U.S. Embassy, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Nov. 11 1996

EVANSDALE —- Fred Morris was just a few days out of Marine boot camp. He was about to be plunged into a day of hell.

“Talk about a lot of growing up in a very short time,” the retired appliance dealer said.

It was May 1975. Morris was a year out of Waterloo East High School. He’d enlisted in the Marine Corps. hoping to become a military policeman and land a permanent job with the Black Hawk County Sheriff’s office.

Instead, he almost became a permanent resident, six feet under, on an island off the coast of Cambodia in Southeast Asia.

South Vietnam had fallen to communist North Vietnam less than two weeks earlier. In neighboring Cambodia, emboldened communist Khmer Rouge forces had seized power and renamed the country Kampuchea. They also seized an American merchant cargo container ship, the SS Mayaguez, and its crew of 39.

President Gerald Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, determined to re-assert American resolve, sent two Marine divisions including Fred Morris, and naval and air forces to retake the ship and free the crew, at Koh Tang Island off the Cambodian coast.

“We had just been embarrassed (in Vietnam) and we wanted to make sure that if anybody attacks the U.S., they know they’re gonna pay a price for it,” Morris said.

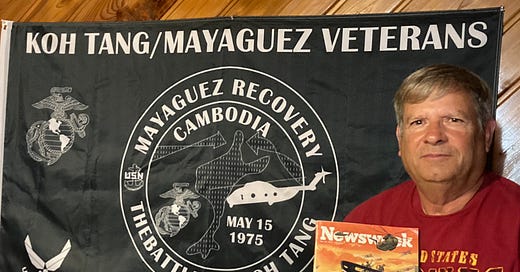

Morris and his comrades were about to become a part of Marine Corps history that is little remembered except by Marines themselves

World War I had the Devil Dogs. World War II had the Sands of Iwo Jima. The Korean War has the “Chosin Few” or the “Frozen Chosin,” at the Chosin Reservoir.

Morris and his buddies were about to become part of the Koh Tang Beach Club. But it was no clambake.

The Mayaguez was retaken and its crew of 39 released after the assault began. But 38 Americans were killed and 50 wounded, including Morris, who was hit by enemy fire while running for the last American helicopter leaving the island. Two comrades pulled him inside. Three other Marines were captured and later executed by the Khmer Rouge. Several helicopters were shot down.

It may have been done for the right reasons, but nearly everything went wrong, Morris said. Much of it stemmed from poor intelligence as to the enemy strength and firepower.

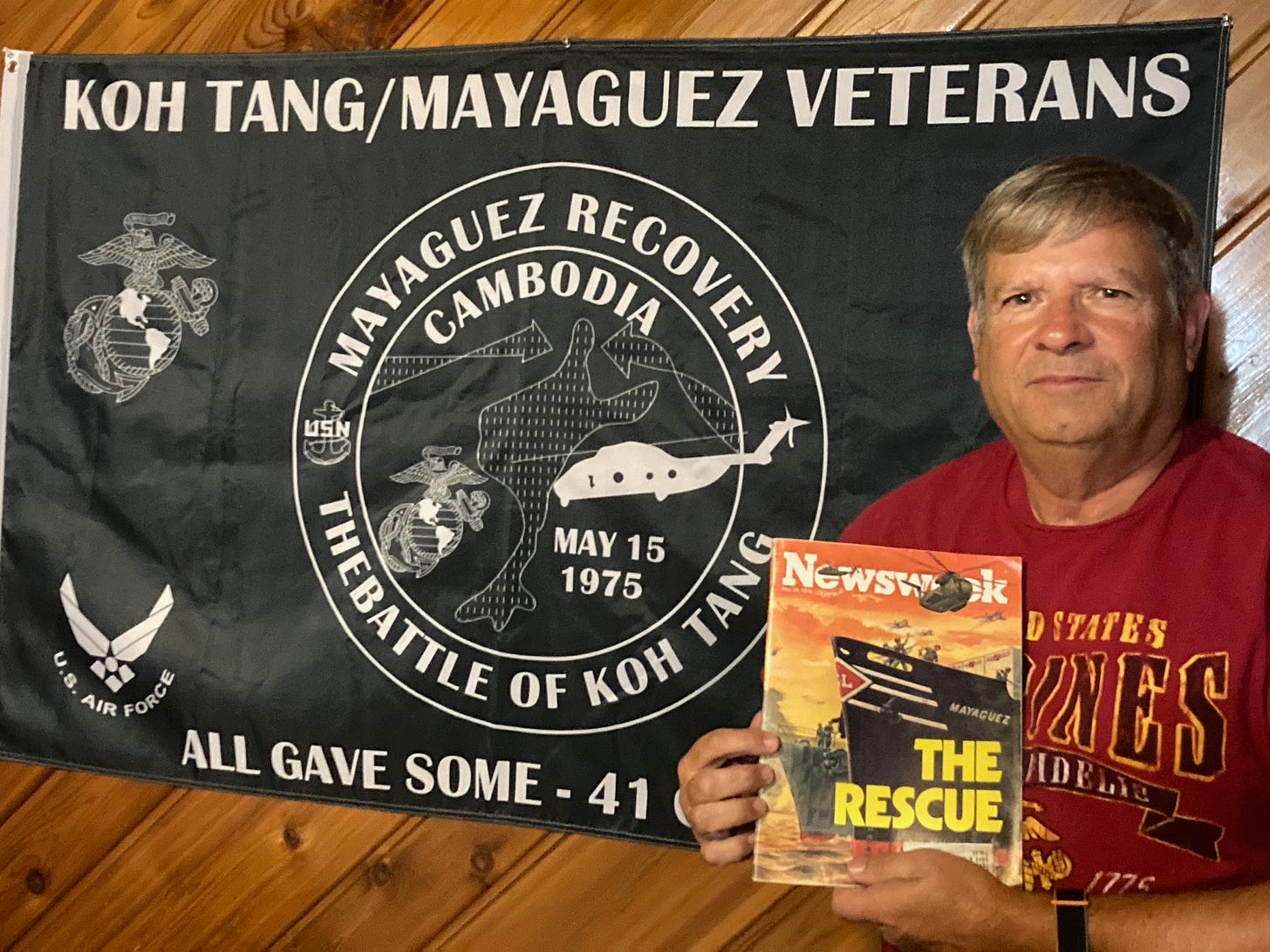

Morris said the Marines were told to expect a platoon-sized Khmer Rouge force, some armed with AK-47 submachine guns. One half of the American force was helicoptered to one side of the island, the other on the opposite side and they were told to “walk to the middle ‘til we find our crew” of the Mayaguez.

Unbeknownst to the Americans, the crew had been taken off the island via fishing boat, escorted by enemy swift boats. The crew was located and released, but not before the first group of Marines had landed on the island. And when Morris and his comrades saw the green tracers from 20 mm anti-aircraft rounds pierce their helicopters, they knew they were in for a stiffer fight than anticipated.

“As we’re landing and you see these major tracers and everything else coming at you, it’s like ‘Okay, that’s no AK-47,’ “ Morris said. “Right off the bat you knew this thing’s not going to be what they advertised. When you’re shooting anti-aircraft at a helicopter from 200 yards, you don’t have much of a chance. That’s why so many of them went down and so many of them were destroyed.”

One of the downed helicopters had just dropped off Morris and some of his comrades on the island. “It never got any elevation. I could see it,” Morris said. “It just sat down in the water and flipped over.”

The helicopter had flown Morris and his comrades to the planned landing spot, but once the craft had committed itself to a hover to let them off, the enemy opened fire.

“We couldn’t hear — these things are pretty noisy inside — but you could see where the rounds were coming into the helicopter,” he recalled. “As it turned around into the sun the rays of light from all these bullet holes are just showing up everywhere.”

Morris said it seemed like it took the helicopter forever to turn around to extend a landing ramp. “I saw a whole lot of bullet holes. Then something hit a hydraulic line or a fuel line and it just started spraying the interior. About that time he sat down, and it was just time to get out of there.

”When we got down, we were in elephant grass three to four feet tall,” he said. “And everybody’s shooting. We’re not doing a lot of shooting,” but trying to determine the direction of fire. The island consisted of triple-canopy jungle not far off the beach. The troops established a space and perimeter no larger than two football fields.

Morris said his own M-16 automatic rifle — which he had only been handed shortly before the operation began — malfunctioned. But he found a replacement in a heavily concealed cache of captured American weapons and ammunition the Khmer Rouge had stored on the island.

“Military ‘intelligence,’ “ Morris said sarcastically with a laugh. The cache was hidden in a cave the side of a bluff below enemy machine gun positions. It was a fortuitous discovery because the Marines each were only allocated two magazines of M-16 ammunition and two grenades, due to the anticipated light resistance.

“Two magazines don’t last very long in combat,” Morris said. “We were out of ammo right away, and luckily, this place had all kinds of ammo.”

Eventually, heavily armed Air Force AC-130 Spectre helicopter gunships were called in to take out much of the enemy positions, followed by a 15,000 pound BLU-82/B “daisy cutter” bomb, designed to clear thick foliage for a landing zone to extract troops by helicopter.

A moonless night fell, making it even more impossible to see in the jungle. Suddenly flares dropped from a helicopter it appear the thick jungle was moving, further disorienting and putting troops on edge.

“We hadn’t had any sleep for 36 hours before we started the mission, and we’d been there 12 hours under some pretty high stress. So now you are just wired, and you’re totally spent at the same time,” Morris said.

Troops began to be evacuated a little at a time via a path through the jungle in the dark. They were told to run for the helicopters when the pitch of their rotors indicated they were on the ground.

“That chopper lands, and you can’t see. We had jungle between us and the beach. I’m running until I’m out of jungle. and the helicopter’s right at the end of this trail. That’s only about 40 yards. I took about two steps and a grenade, a mortar, something, blew up in front of me. That’s where I got all the shrapnel, and it knocked me off my feet. The adrenaline was such that, there’s no way I’m gonna miss that helicopter. I can’t hear,” from shell shock.

“All of a sudden, I’m running back into the jungle,” disoriented by the blast, “So I backed up. I mean, I’ve never run so fast in my life and I’m heading for this helicopter. And they don’t have any lights on. And when I get there, one foot hits the ramp, and the other foot misses it and I go right into the side of the helicopter.”

A gunnery sergeant and another Marine dragged him onto the helicopter.

A helicopter rescue crewman who was looking for any stragglers before takeoff nearly fell off the helicopter because the ramp hadn’t been locked. Hanging on the ramp, he was dragged on by his radio headset. The helicopter landed on the carrier USS Coral Sea. Morris said he was so disoriented and on edge he thought the helicopter was going to crash when it picked up altitude to land on the carrier deck, and he thought the landing lights were enemy tracers.

Then, suddenly, they landed on the carrier deck and it was over.

“That’s a long day,” he said.

They’d been on the island 14 hours. The pilot of the helicopter which rescued them, aware of the Marines’ dire situation, unloaded a group of Marines he was already carrying onto a small destroyer, touching one wheel in the deck, his rotors coming within inches of the small destroyer’s conning tower. It was enough to unload them, without landing, through a gunner door, so he could go back and retrieve Morris and 29 remaining comrades.

"I’m on the last load out because he took two loads. If he hadn’t have done that, there’s no last load,” Morris said. “I wouldn’t have gotten off the island.”

Fiftieth anniversary commemorative events of the Mayaguez incident are planned for Friday, May 9 at the Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base in Georgia, where one of the craft used in the operation is being retired. Morris is scheduled to speak as well as a fellow Iowan, Ambassador Kenneth Quinn of Des Moines, who erected a memorial to those lost in the Mayaguez incident while he was ambassador to Cambodia in the 1990s.

In a speech at the Iowa Veterans Home this past week honoring Vietnam veterans, Quinn talked about how he cut through red tape to get the memorial erected at the U.S. Embassy in the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh and how he helped arrange for recovery crews to look for remains of Americans who died in the battle.

Morris is also slated to go to Washington, D.C. May 12-16 for a 50th anniversary reunion of his comrades and commemoration of the battle at Arlington National Cemetery.

There are a number of inconsistences regarding recognition for the Koh Tang/Mayaguez Marines. While the names of those killed in the battle were added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall in Washington, D.C., the units involved never received a presidential unit citation.

It took Morris more than 30 years to receive a Purple Heart for his wounds which complicated his ongoing personal struggle for treatment from the Veterans Administration.

Nor is the Mayaguez incident listed with other Marine operations at the base of the U.S. Marine Corps memorial near Arlington cemetery — the giant statue of the Iwo Jima flag raising during World War II.

“We’re at the tail end of Vietnam — they say ‘You’re Vietnam.’ You feel guilty about that,” Morris said. “I wasn’t in Vietnam.”

But it wasn’t worth making a fuss over at the time. “Back then, you weren’t real proud of serving” due to public sentiment against the war, which was taken out on troops. “When you come home, you were baby rapers and everything else.

Also, he said, “When you play politics, the soldiers lose.”

But now, “We’re over it,” he said. “You used to go and recap mission debriefs and now you’re just getting together with friends. Very little chest pounding any more. We’re too old for that,” he said laughing.

“I’m proud of what I did and I wouldn’t have it any other way,” he said, “It’s not about the recognition. I’m glad I served. I’m glad I came back.”

Pat Kinney is a freelance writer and former longtime news staffer with the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier and, prior to that, several years at the Ames Tribune. He is currently an oral historian with the Grout Museum District in Waterloo. His “View from the Cedar Valley” column is part of “Iowa Writers Collaborative,” a collection of news and opinion writers from around the state who previously and currently work with a host of Iowa newspapers, news organizations and other publications. They are listed here. Clink on their individual links to check them out, subscribe for free - and, if you believe in the value of quality journalism, support this column and/or any of theirs with a paid subscription. Thank you.