Bringing Birmingham lessons to Waterloo

Black Hawk County Democrats chair lost childhood neighbor in 1963 church bombing

WATERLOO — Vikki Brown is an energetic, outgoing, warm person.

”I’m a hugger,” she’ll tell you.

Beneath her outward joy is a steeled determination, tempered in a crucible of the American civil rights movement. — Birmingham, Ala., where she grew up in the early 1960s.

“They called it ‘Bombingham,’ “ she said.

It was so named for the number of bombings in the city, where racial tensions were high.

”Where I lived, you could hear the bombs go off because they were always bombing churches...It was very turbulent times,” she said.

Brown is in her fifth term as chairwoman of the Black Hawk County Democrats, having been re-elected this spring. She’s lived in Waterloo, where a daughter lives, since 2006, but she had a lifetime of experience in civic action before that.

In fact, she’s been fighting nearly her whole life for justice — dating back to her childhood in Birmingham, where the parents of many Black families had jobs in military service to this country.

“I was born during the Jim Crow era, and there were certain things you couldn’t and did not do,” Brown said. “Our parents would always say, ‘Make certain that you are home before it gets dark.’ During that time, the KKK was very prevalent and little Black boys and girls would go missing and never be found. The KKK practiced their lynchings and tar-and-featherings.”

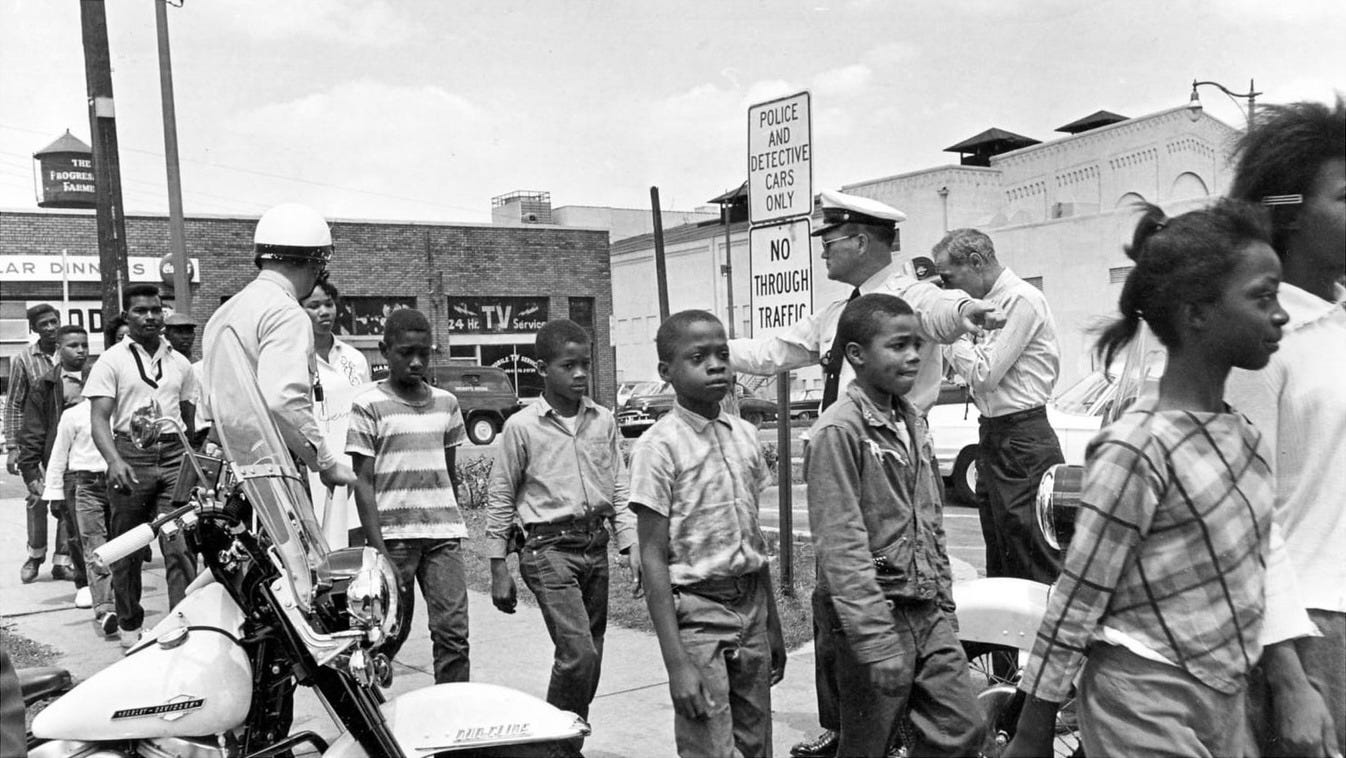

Despite that, “I was a bit of rebel,” she said. One day, after an early dismissal from school due to the situation in town, Brown and some of her more inquisitive classmates decided to go downtown to see what was going on.

“We went downtown to the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church,” she said. “We really didn’t know what was going on, but we were excited because we’d never seen that many people together ever.”

The children were placed at the front of the line. “We thought we were special people,” Brown said. “We didn’t know what we were going to be met with.

“We were met with fire hoses, police batons and police dogs,” she said. “Although they were holding the police dogs, they were able to bite us. To this day I still carry some of the bite marks on my legs.

“We were arrested along with a lot of the other adults,” Brown said, “We didn’t get back to our homes until later that night or early the next day.

It became known as the “Children’s Crusade.” More than 1,000 children walked out of their classes and marched against segregation. The children were jailed on the order of Public Safety Director Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor and released. They returned the next day and were jailed again, drawing nonviolent protests from adults, as the jail was packed to capacity.

“This is when I came to the realization of what was going on, of what my mom was afraid of,” Brown said. "

More trouble came in September — deadly trouble.

“One of my friends, neighborhood acquaintances, she was murdered,” Brown said.

Carol Denise McNair was just 11 years old when she and three other girls were killed in the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing on Sept. 15, 1963.

“The Ku Klux Klan blew up the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church,” Brown said. According to historic accounts, an investigation revealed four members of the United Klans of America had planted at least 15 sticks of dynamite with a timing fuse by the church steps near the basement. Between 14 and 22 other people were injured.

“That just hurt me to the core,” she said. She couldn’t understand why her friend died any more than the events of the previous May. “My parents tried to explain to me what was going on. They didn’t want Black people to have voting rights and civil rights; we couldn’t sit at the same lunch counters. They didn’t want us to have any kind of rights and that’s why the marches were taking place.”

It was one of a series of rapidly unfolding events in the American civil rights movement in the summer of 1963. It was less than a month after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It was three months after President Kennedy sent to Congress comprehensive civil rights legislation after dispatching troops to enforce a court order desegregating the University of Alabama.

Brown also recalled that on family travels with her father between military bases, at service station stops for gas, “we couldn’t get out and use the restroom or anything. We couldn’t buy snacks or anything; that’s why my mom always packed a lunch. We would have to get back on the highway and pull off the highway and go in the bushes.”

“And I wanted to know, ‘Why did they want to murder us? Why did they want to kill Denise?’ Denise was my friend, my neighbor,” Brown said. “They said they were trying to murder as many people as they could with that bomb. I just made up my mind, this isn’t right; what could I do?

“My mom said, ‘You could die’ I said, ‘I’m willing to give my life for this,’ “ she recalled.

Though her parents discouraged her from political activity out of concern for her personal safety, an older sister urged their parents to let her get involved.

”Ever since then I’ve been marching and doing things,” Brown said. “They way to change things is to help with elections.”

When she moved to Michigan in her early 20s after getting married and being attracted there by employment prospects in the auto industry, she worked on the campaign of Detroit’s first Black mayor, Coleman Young, in 1974,

’That gave me my political prowess, and that’s what I’ve been doing ever since,” she said. “I went to one of his rallies, and what drew me to him was he was very outspoken, to say the least. And I like that,” especially given the conventions of society she’d been forced to accept in the South. “I felt he was speaking from the heart. I signed up to join his campaign and it’s been a political ride ever since.”

She continued to work on numerous other local campaigns, as well as then-U.S. Sen. Barack Obama’s presidential campaign in 2008, and his re-election as president in 2012. That earned her a trip to the White House. In 2016 she was an outreach coordinator for Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. She was a delegate to the 2024 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

She was first elected county Democratic chair in 2017. But she doesn’t want the party to be a ideological echo chamber. “In this role I do reach out to other people besides the Democrats. We all have some of the same ideals. But I am a Democrat.” She recently participated in a march for immigrant and refugee rights in downtown Waterloo, sponsored by Waterloo’s Catholic Hispanic ministry.

She’s demurred at suggestions she seek public office herself. “I just found myself drawn to helping people achieve their goals, which is, get elected,” she said. “I’m a person that likes to stay in the background and help people get elected.

“I honestly think this work chose me,” she said. “At 11 years old, you don’t know what you’re doing. Especially when Denise was murdered, I just felt like I grew up some. I came into my own, to know, this isn’t right.

She’s chosen to live in Waterloo because “it’s just the closeness, the camaraderie,” she said. “I always related to so many people that were here. My roots are Alabama and Mississippi, and there’s so many people from Mississippi. We call each other cousins.”

She’s organizing an event, “Good Trouble in the Cedar Valley: Honoring the Legacy of John Lewis and Waterloo’s Civil Rights Icons,” to be held 5 to 7 p.m. Thursday, July 17 at the Waterloo Center for the Arts.

The event is being held on the fifth anniversary of the death of U.S. Rep. John Lewis, honoring the late civil rights leader and Georgia congressman, as well as past and longtime local civil rights leaders and local recipients of the 2025 John Lewis Youth Leadership Award.

It is part of the John Lewis National Day of Commemoration and Action. The event is hosted by the Black Hawk County NAACP, Black Hawk County Democrats and sponsored by Indivisible Iowa Black Hawk County.

Brown admits to being haunted a bit by the memories of 1963 — but they serve to motivate her at the same time.

“Often I have those times. The trauma persists,” she said. “Especially in those silent moments, when you see so much of what’s going on in the world, and then you think about your personal history, and it’s so hurtful. Because I can flash back to those dogs and those fire hoses, and the batons. And that’s not something that I want to happen to anybody. It gives you the motivation to carry on.”

Pat Kinney is a freelance writer and former longtime news staffer with the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier and, prior to that, several years at the Ames Tribune. He is currently an oral historian with the Grout Museum District in Waterloo. His “View from the Cedar Valley” column is part of “Iowa Writers Collaborative,” a collection of news and opinion writers from around the state who previously and currently work with a host of Iowa newspapers, news organizations and other publications. They are listed here. Clink on their individual links to check them out, subscribe for free - and, if you believe in the value of quality journalism, support this column and/or any of theirs with a paid subscription. Thank you.

What an excellent profile!

We are so lucky to have Vikki Brown here in the Cedar Valley! Love you Miss Vikki! 💙