“If you want peace, work for justice.” — Pope Paul VI, 1972

WATERLOO — When I began covering local stories about child sexual abuse by Catholic priests and others in vowed religious vocations for the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier in 2004-05, one survivor of such abuse very firmly and poignantly drove home his point to me.

The survivor, who happened to be a former police officer, sent me a smiling, grade-school photo of himself and wrote:

“Just remember, your son is as old as I was when I was abused.”

I never forgot that.

I’ve said to friends, only half kiddingly, that Catholic conscience and journalism ethics can be a very burdensome combination.

It’s probably why I pursued those stories. I remain an imperfect practicing Catholic but hold dear the faith I was raised with. I am very grateful to several individual priests and nuns who helped me through some difficult personal periods. Some even encouraged and inspired me in my profession — starting with my high school journalism teacher, who was a nun. My divorced single-parent self-employed mom was the most devout Catholic I knew. She was a role model for me in faith and life as she broke a lot of barriers in her own unassuming but determined way.

It’s because of those folks and, as a journalist who’s trained to question authority, see the big picture and report the bad with the good, that I do believe the institutional church, like any large public or private institution, needs to be questioned and held accountable - and practice what it preaches, out of respect to the folks who did and lived their faith. It’s better for the church, better for the faithful, better for the larger community and, quite frankly, it didn’t happen enough within the church on this issue.

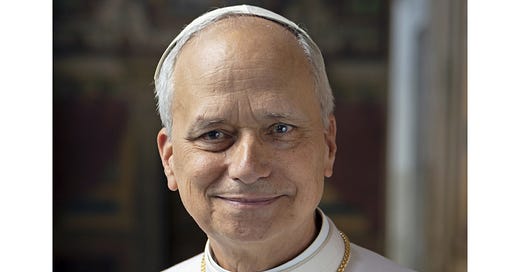

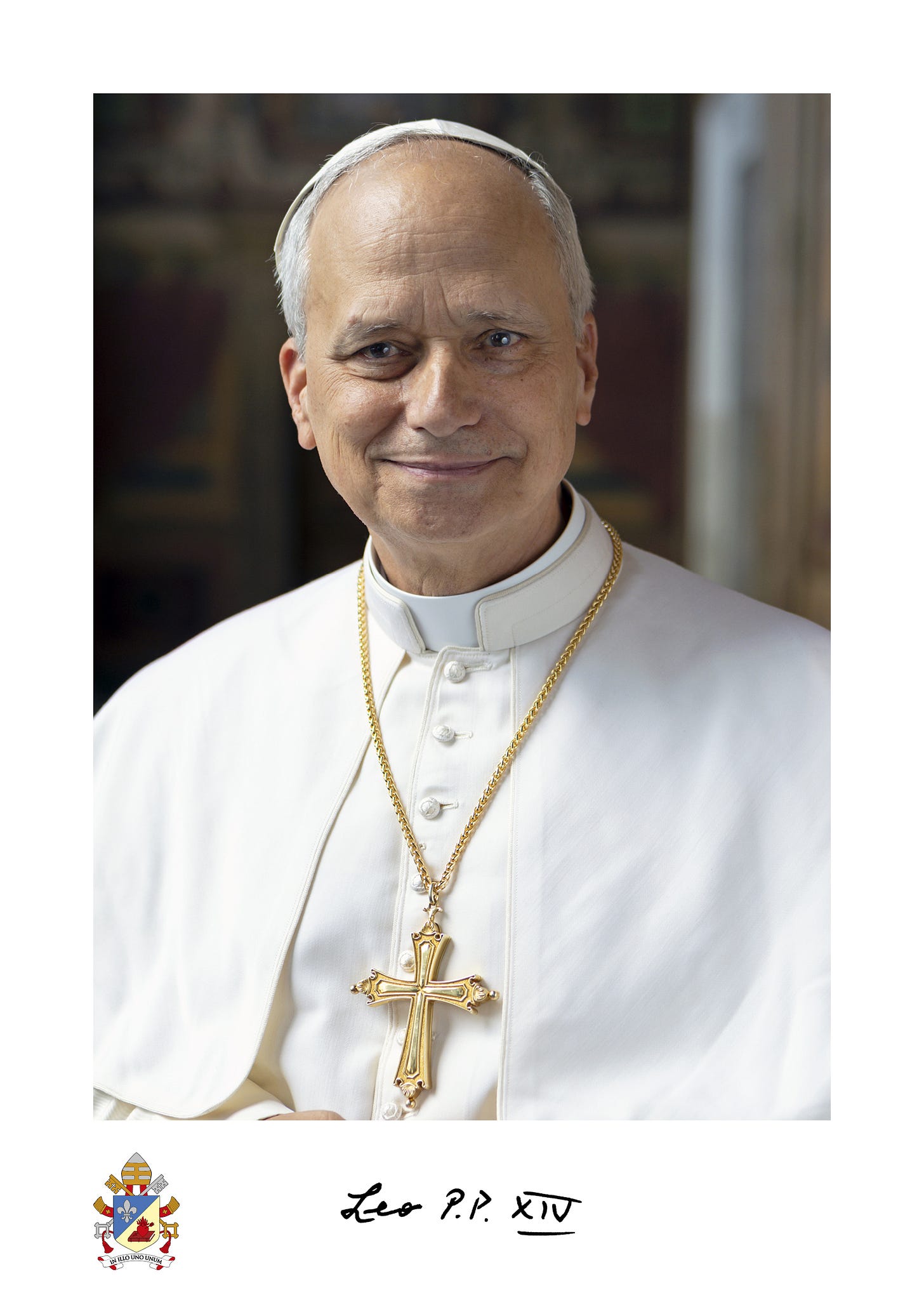

The election of Pope Leo XIV is no different. While I was surprised and pleased at his election, as many were, sure enough, a statement from the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP) popped into my email. I also looked up the statement by BishopAccountability.org, a site that watches how the institutional church handles alleged incidents of abuse and sexual misconduct with seminarians and other vulnerable adults.

While the installation of a new pope is understandably a time for hope and rejoicing for many, I invite folks to read the statements by Bishop Accountability, linked here and SNAP, linked here, as well as SNAP's letter to the new pope on behalf of survivors, linked here.

I understand folks may agree in whole, in part, or maybe not at all with these statements or their tone. However, I feel compelled as a matter of journalistic balance and personal conscience to point out these views exist and not be dismissive of them. Some people are hurting. Their voices must be taken into account if the church is to move forward as a force for peace and justice in the world.

It’s something the church continues to wrestle with. The same day Pope Leo XIV gave his first general audience in Vatican City, the Archdiocese of New Orleans agreed to pay nearly $180 million to victims of clergy sexual abuse, the latest in a string of settlements by the Catholic Church. That Associated Press story is linked here.

Locally, the church has not been sacrosanct from this issue. In several settlements from 2006 through 2013, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Dubuque, which covers the northeast quadrant of Iowa, paid out more than $17.5 million, plus counseling expenses, on 83 claims of clergy sex abuse involving clients represented by the Dutton law firm of Waterloo, which has handled the bulk of claims within the Dubuque archdiocese.

Many of the claims involved alleged incidents which were decades old; many of the offending priests were deceased. None living were practicing priests; some were removed from priestly duties by the archdiocese and at least two were defrocked by the Vatican. The archdiocese ordered mandatory sex abuse prevention training for its employees, and new reports dropped off drastically in subsequent years.

The archdiocese established a review board to hear complaints and maintains a registry of priests against whom credible accusations of abuse have bene made. The

”Table of Accused Priests” can be found here. The archdiocese also has worked privately with survivors and issued several public apologies in conjunction with the settlements.

But last year, a criminal case against a former archdiocesan priest involving incidents in Dubuque in the 1980s was dismissed because the statute of limitations had expired for criminal prosecution of those charges. The accused denied the charges. Periodic calls by some in the Iowa Legislature for changes to the statute of limitations have gone unanswered. For many survivors who are unable, for whatever reason, to come forward with such criminal accusations as minors, civil action once they are of age remains a favored if not the only recourse if they find the response by the institutional church to be unsatisfactory.

The Davenport Diocese settled its claims by going into bankruptcy reorganization from 2008-11 for $37 million and took remedial steps similar to Dubuque, in concurrence with the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Information on that settlement can be found here.

But the issue persists on a wide scale, as evidenced by the recent settlement in New Orleans. And it includes religious orders of priests and other vowed religious such as monks and nuns, including missionaries, who don’t answer directly to an individual diocese or archdiocese. The buck stops with the pope.

Those opposed to the new pope will try to use this issue to undermine him -- and have already been making rumblings to that effect. But in fact, as the allegations themselves show, this has been an institutional failure of the church dating back decades — and long before the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, which some critics have derided for its supposed permissive modernizations. The revelations may be fairly recent, but the actions aren’t. The same is true in coaching and other secular professions.

Our new Holy Father must be proactive in addressing this issue, even as he takes on his awesome responsibilities on a number of fronts. I suspect he knows that, as did his two immediate predecessors who at least started to cleanse the temple.

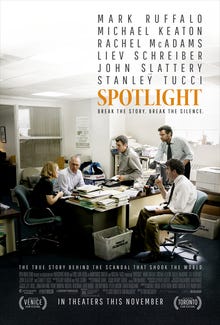

There was a very significant line in the 2015 movie “Spotlight,” an Oscar-winning film about this issue and the Boston Globe reporters who, in 2003, finally reported it in the detail it deserved and won a Pulitzer Prize for community service.

At one point toward the end of movie, Michael Keaton, as “Spotlight” reporting team leader Walter “Robbie” Robinson, is asked by an indignant friend and a reluctant source, played by John Slattery, why it took the Globe so long to get on this story, which had previously been handled as isolated incidents involving individual priests.

Liev Schreiber, as then-Boston Globe editor Marty Baron, says to the remorseful Spotlight team, “Sometimes it's easy to forget that we spend most of our time stumbling around the dark. Suddenly, a light gets turned on and there's a fair share of blame to go around.” He then says, “I can't speak to what happened before I arrived, but all of you have done some very good reporting here. Reporting that I believe is going to have an immediate and considerable impact on our readers. For me, this kind of story is why we do this.”

That statement about a light getting turned on — whether Baron really said it, or if it’s the product of a good screenwriter — is absolutely true. It doesn’t only apply to journalists but all of our public institutions, including the church and the criminal justice system, when it comes to protecting our young people. That also applies to protecting vulnerable adults such as idealistic seminarians aspiring to make a difference for good in people’s lives and everyday churchgoers who want to feel safe going to their pastor or any clergy for help.

The light’s on now. Let’s not take it for granted but focus it. Let’s protect our kids. Let’s protect the vulnerable, the broken, and the young people who are called to ministry because they believe in a higher purpose.

It’s a challenge, and, at the same time, a tremendous opportunity.

”Then you will go on your way in safety, and your foot will not stumble,” — Proverbs 3:23

Pat Kinney is a freelance writer and former longtime news staffer with the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier and, prior to that, several years at the Ames Tribune. He is currently an oral historian with the Grout Museum District in Waterloo. His “View from the Cedar Valley” column is part of “Iowa Writers Collaborative,” a collection of news and opinion writers from around the state who previously and currently work with a host of Iowa newspapers, news organizations and other publications. They are listed here. Clink on their individual links to check them out, subscribe for free - and, if you believe in the value of quality journalism, support this column and/or any of theirs with a paid subscription. Thank you.

As a clergy sexual abuse survivor, abused at the tender age of 7, and I had one of the first cases with the Catholic Church in the country in 1991, you have done an outstanding job capturing the history of this horrific issue that many want to forgive and forget. I applaud your willingness to keep speaking up about the darkness too many of us have faced alone with our families, and friends praying for justice. When the whole story of the cover-up is out, all abusing priests named, the truth will set us all free. The Church is continuing to minimize and cover up in many parts of the world. Let's keep talking and writing, praying and hoping the gorgeous light infiltrates the darkness that has harmed thousands around the world.

Patricia Gallagher Marchant

Excellent column, Pat. One of the best I’ve read on this subject.